There are 43 blind-inclusive schools in Uganda, and almost all schools practice Inclusive Education, IE policy, a policy advanced by UNESCO to have all children, regardless of their ability or other characteristics, aided to learn and develop their full potential.

This means for the IE policy to have meaning, the education system should give the learners with visual impairment the digital tools and skills opportunities to realize their dreams. However, the IE policy in Uganda is still in the development stage, making IE a mere ambition, rather than a tangible plan for action, according to a 2017 report by the Uganda Society of Disabled Children.

Persons with visual impairment can use a computer installed with Job Access with Speech, JAWS, a screen reader that works with Windows operating systems and provides text-to-speech and braille output. Victor Reader Stream is a handheld digital media recorder and player that enables a user to listen to books, newspapers, and online reference tools through a tactile keypad. A talking book player (plextalk) is another digital tool that uses features that are friendly to persons with visual impairment.

Joyce Ajok, the head of the blind annex at Gulu Primary School, says they have struggled to educate the 55 learners with visual impairment due to the shortage of these digital tools.

Two years ago, a charity organization that provides assistive technology for children with visual impairment gave them two laptops installed with JAWS, but the JAWS license expired in March 2020 and the department has since failed to reinstall it.

Installing a JAWS software costs $1,000 (above UGX3.5 million). This amount is more than the (UGX 2million) subvention grant given by the government for the department to pay for costs of light meals, scholastic materials, and medical care for three months.

In March 2021, the Ministry of Education in partnership with UNICEF also donated two laptops to the blind annex, but without the JAWS, says Ajok.

“The laptops are now being used by the teachers who have sight. A Victor Reader Stream that was donated by UNICEF in 2018 was used by the learners in a group.”

“If well-wishers could get a computer or a recorder per child, then it could ease our work. But now, rewarding learning by children with visual impairment solely relies on their parents’ financial capacity and will,” Ajok says.

Charles Byekwaso, the Executive Director of Uganda National Association of the Blind (UNAB), agrees that the JAWs software is expensive for learners with visual impairment and many cannot afford it. He says UNAB is talking with the producers of the software for them to sell at a subsidized price.

“You know the license for JAWS is expensive. It is not easy and at times when you get a subsidized one, it is around 800 dollars. It is not easy I agree with them. But we are trying to advocate to see that those prices are reduced. And sometimes people find no way of reducing their prices. But we are trying to engage the companies that produce software to reduce [or price] at give us at a subsidized price,” he says.

The 2017 National ICT policy report notes that barriers such as high costs of setting up ICT infrastructure and buying assistive devices, limit access and availability of the tools to PWDs in Uganda.

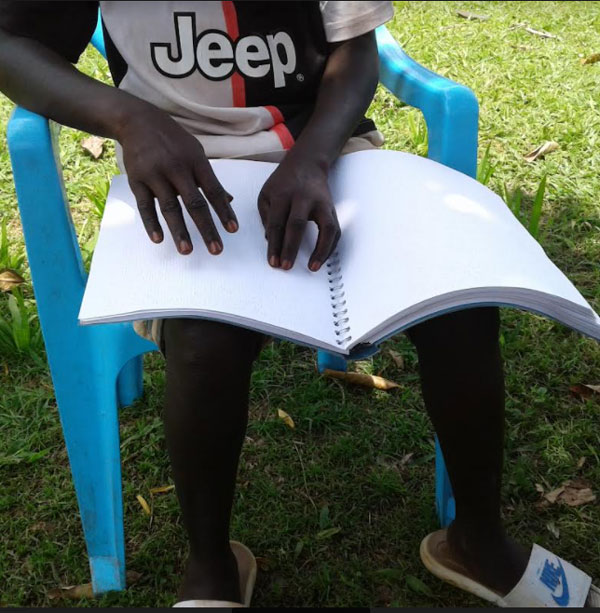

Byekwaso says since learning is now done from home and online, UNAB is advocating for all learning materials to be brailled, so that it is accessed by the learners with visual impairment.

“But we have not succeeded. The National Curriculum Development Center and Sense International did some part but it was not much. So, we are still advocating that all the materials which are given out to other students can be given to other learners with visual impairment. Not halfway, but all of it. Because if they put it halfway then people [with visual impairment] are not going to perform well when it comes to time for examinations,” Byekwaso says.

Sarah Ayesiga, the assistant commissioner for inclusive and non-formal education in the Ministry of Education and Sports agrees that learning is more difficult for children with visual impairment, especially when they have to rely on radio and television, which makes them miss some aspects of the lessons such as diagrams and maps.

“Yes, it is true. Even for the primary [pupils], I know there are those children who are learning from TV, because if there is a map and the teachers says, you look at this with the faded area, the other person even if he is on TV, he will not be able to see,” Ayesiga says.

“Those people [teachers] we have been telling them that if we could devise other means of designing another question. If there is a question that involves graph or map reading. We could have another question for that what who is visually impaired and specify it. So those are things we are trying, to ensure that those learners are also participating equitably,” Ayesiga says.

“Yes, there are those issues which are so pertinent. But as a Ministry, we have transcribed the print content into braille. We have also put that content on memory cards, where teachers have been recorded teaching, and we have bought or given MP3 players, or victor readers. So, we have given those to primary schools and a few secondary schools because we didn’t have money to replicate or reproduce learning materials for all the learners in all the secondary schools. And even the one for primary [pupils] are not enough,” Ayesiga says.

However, Lucy Akech, a mother to Ogenrwot, says her son had not been given any recorded home-learning materials for the 16 months.

Ayesiga then explained that the materials were delivered to the respective schools because they could not distribute to every child with visual impairment. Meaning, even those learners at home, those with visual impairment have to travel to their respective schools to use them from there.

“We have delivered those materials but they are still at school because we cannot give them to every learner. So, it means those learners will go and benefit from those home learning materials from school,” Ayesiga says.

Joyce Ajok, the Head of the Department of Gulu Primary School blind annex, agreed that they received eight Perkins braillers from the Ministry of Education in June 2021, but they are yet to start using them.

“The braillers are still in the headteacher’s office. I was informed that other materials were also brought, but I have not seen them all. They have not yet opened them all for us,” Ajok says.

**********

✳ This reporting was supported by Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) as part of the Isu Elihle Awards. This is Part one.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

fantastic points altogether, you just received a new reader.

What might you suggest about your put up that you just made some days ago?

Any positive?