The authors argued that dictatorships collapsed for all sorts of reasons. When this happens, achievement of a certain threshold of development – equal to about $8,000 per person a year in 2005 prices or equivalent currencies – protects new democracies from backsliding. Below this level of development, however, countries that experienced regime transitions had little chance of sustained democratic stability. In this view, poor African societies may experience a regime transition from autocracy to the establishment of democratic constitutions and multiparty elections, but only for a short period. Their odds of flourishing remain slim.

For example, democracy in Mali collapsed following a military coup d’etat in March 2012, proving as fragile as the local Tuareg nomad settlements built upon shifting Sahara sand dunes.

Is richer more democratic?

If development is the root cause of the problem, then electoral malpractices such as coercion, vote-buying and fraud can be expected to be particularly severe in the poorest societies in Africa. But are they? This is where the EIP provides insights.

The 2015 EIP annual report compares the risks of flawed and failed elections, and how far countries around the world meet international standards. It gathers assessments from over 2,000 experts to evaluate the integrity of all 180 national parliamentary and presidential contests held between July 1, 2012 and December 31, 2015 in 139 countries worldwide, and it generates an overall 100-point Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index. Contests are further classified into flawed contests (those scoring 40-49 on the 100-point scale) and failed elections (those scoring less than 40).

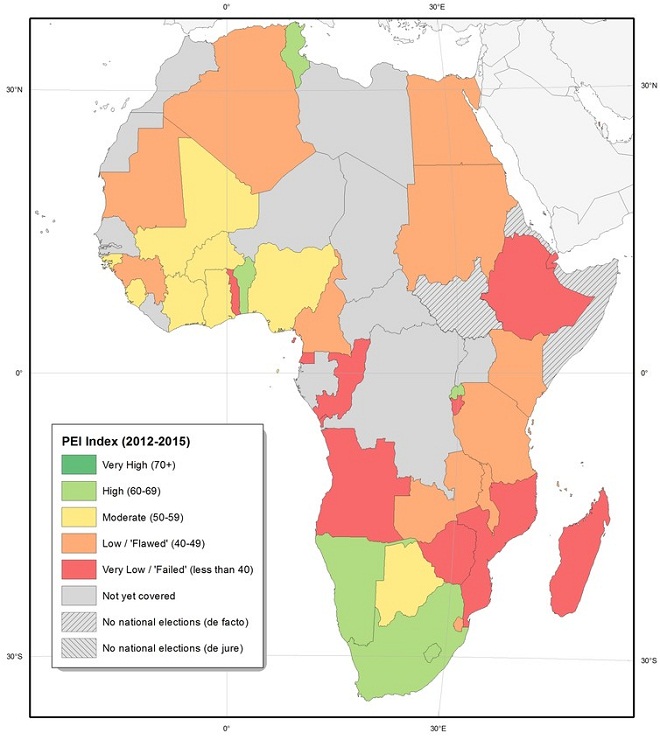

PEI Index Africa Author provided

To summarize the evidence in the region, it shows relatively positive scores for electoral integrity in Benin, Mauritius, Lesotho, South Africa and Namibia. All had high integrity.

Unfortunately, more than half the African states included in the survey have flawed contests (with low scores for integrity), with Burundi, Equatorial Guinea and Ethiopia rated as failed elections – and some of the lowest ratings for integrity in any country around the globe.

But is development the key?

Within Africa, there is little evidence that wealth and poverty are correlated with levels of electoral integrity. Thus, failed contests include oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, along with poor Burundi, Ethiopia and Djibouti. Similarly, the flawed category includes elections in moderate-income Algeria as well as low-income Mauritania and Malawi, while the high-integrity contests include both low-income Benin and the more prosperous Mauritius.

Of course, the evidence within Africa provides a limited test of both the Lipset thesis and the Limogi and Przeworski argument, because nearly all states fall into the less developed category. A broader comparison of elections across the whole world suggests a positive link between economic development and the quality of elections.

Affluent Norway, Switzerland and the Netherlands have high-quality elections, according to experts, while low-income Haiti, Ethiopia and Cambodia score poorly, with just a few outliers, like Kuwait and Singapore.

What is to be done?

Elections are the heart of the representative process. Flawed contests damage party competition, democratic governance and fundamental human rights.

And that’s not all. As shown in my book, `Why Electoral Integrity Matters’, malpractices have important consequences by deepening public mistrust of electoral authorities, political parties and parliaments, which, in turn, depresses voter turnout and catalyzes protest activism.

Rather than abandoning support for elections in the face of these challenges, the international community needs to double down on its investment.

According to AidData, roughly half a million U.S. dollars of official developmental assistance are spent annually on providing electoral assistance worldwide. While many African elections are indeed deeply flawed today, the EIP evidence suggests that poverty is not an insurmountable barrier to elections with integrity.

Pippa Norrisis an ARC Laureate Fellow, Professor of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney and McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics, Harvard University – theconversation.com

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price