Trials on the up

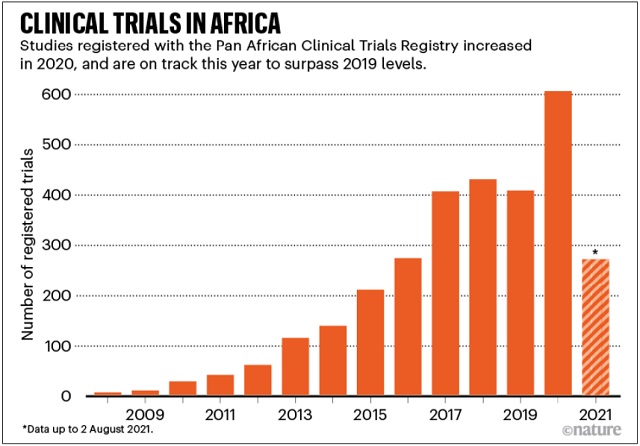

The coronavirus pandemic has given clinical research in the African continent a boost. Vaccinologist Duduzile Ndwandwe tracks research on experimental treatments at Cochrane South Africa — part of the international group that reviews health evidence — and says that the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry registered a total of 606 clinical trials in 2020, compared with 408 in 2019. By August this year, it had registered 271, including trials for both vaccines and drugs.

“We’ve seen lots of trials expanding with COVID-19,” Ndwandwe says.

Trials for coronavirus treatments are still lacking, however. In March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) launched its flagship Solidarity trial, a global study of four potential COVID-19 treatments. Only two African countries participated in the first phase of the study. Challenges in providing health-care services for severely ill patients precluded most nations from joining, says Quarraisha Abdool Karim, a clinical epidemiologist at Columbia University in New York City who is based in Durban, South Africa.

“It was an important missed opportunity,” she says, but it laid the groundwork for more COVID-19 treatment trials. In August, the WHO announced the next phase of the Solidarity trial, which will test three other drugs. Five more African countries are participating.

The NACOVID trial that Fowotade worked on aimed to test its combination therapy on 98 people in Ibadan and three other sites in Nigeria. People in that study were given the antiretrovirals atazanavir and ritonavir, and an antiparasitic drug called nitazoxanide. Even though it didn’t meet its recruitment goal, Olagunju says that the teams involved are preparing a manuscript for publication and are hopeful that the data will provide some insight about the drugs’ effectiveness.

The fight to manufacture COVID vaccines in lower-income countries

South Africa’s ReACT trial, sponsored by the South Korean drug company Shin Poong Pharmaceutical in Seoul, aims to test four repurposed drug combinations: the antimalarial therapies artesunate–amodiaquine and pyronaridine–artesunate; the influenza antiviral favipiravir, given with nitazoxanide; and sofosbuvir and daclatasvir, an antiviral combination typically used to treat hepatitis C.

Using repurposed drugs is highly attractive to many researchers, because it could be the most viable route to rapidly finding treatments that can be distributed easily. Africa’s lack of infrastructure for pharmaceutical research, development and manufacturing means that countries cannot readily test new compounds and mass-produce drugs. Such efforts are crucial, says Nadia Sam-Agudu, a specialist in paediatric infectious diseases at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, who works at the Institute of Human Virology Nigeria in Abuja. “If effective, these treatments may prevent severe disease and hospitalisation, as well as potentially (stop) onward transmission,” she adds.

The continent’s largest trial, ANTICOV, was launched in September 2020 in the hope that early treatments could prevent COVID-19 from overwhelming the fragile health-care systems in Africa. It has currently enrolled more than 500 participants across 14 sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique. It aims to eventually recruit 3,000 participants across 13 countries.

ANTICOV is testing the efficacy of two combination treatments that have seen mixed results elsewhere. The first blends nitazoxanide with inhaled ciclesonide, a corticosteroid used to treat asthma. The second combines artesunate–amodiaquine with the antiparasitic drug ivermectin.

Ivermectin, which is used in veterinary medicine and to treat some neglected tropical diseases in humans, has become controversial in many countries. Individuals and politicians have been demanding access to it for the treatment of COVID-19 on the basis of anecdotal and scant scientific evidence about its efficacy. Some of the data supporting its use are questionable. A large study in Egypt that supported administering ivermectin in people with COVID-19 was withdrawn by the preprint server where it was published amid accusations of data irregularities and plagiarism. (The authors of the study have argued they were not given an opportunity by the publishers to defend themselves.) A recent systematic review by the Cochrane Infectious Disease Group found no evidence to support ivermectin’s use for treating COVID-19 infections.

Nathalie Strub-Wourgaft, who heads the DNDi’s COVID-19 activities, says there are legitimate reasons to test the drug in Africa. She and her colleagues are hopeful that it might act as an anti-inflammatory when given alongside the antimalaria drugs. And the DNDi is poised to test other drugs if this combination is found lacking.

“The issue of ivermectin has been politicised,” says epidemiologist Salim Abdool Karim, director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), headquartered in Durban. “But if the trials in Africa can help resolve that or make an important contribution, then that’s a good idea.”

Strub-Wourgaft says that the combination of nitazoxanide and ciclesonide looks promising on the basis of existing data so far. “We have encouraging preclinical and clinical data that supported our selection for this combination,” she says. After an interim analysis last September, Strub-Wourgaft says ANTICOV is preparing to test a new arm, and will continue with the two existing treatment arms.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price