COMMENT | ANDREW PI BESI | In 1974, the Congo’s grand dictator completed his “Africanisation” of the Congo by renaming it Zaire. He discarded his birth name and crowned himself Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga — “the invincible warrior cock who leaves no chick intact.”

To prove his invincibility, he proclaimed, “In our African tradition, there are never two chiefs. There may be a natural heir to the chief, but has anyone ever known a village that has two chiefs? That is why we Congolese, in the desire to conform to our traditions, have resolved to group all the energies of our citizens under the banner of a single national party.”

At the time, mineral and commodity prices were booming. Zaire was flush with cash — a balanced budget, a favourable balance of trade, and international optimism that it was on the cusp of realising its vast potential.

Then, as if cursed by its own conceit, Zaire began to choke on the yolk of grand corruption. The aspirations of its people were systematically trivialised and trampled by the ruling elite. By 1978, Mobutu’s Zaire, like its northern neighbour ruled by Bokassa, was doomed.

Across the continent, Mozambique offered a contrasting picture. In 1975, FRELIMO’s long war against the Portuguese finally ended. Founded in 1962 by Eduardo Mondlane, FRELIMO owed much to his rare blend of scholarship and revolutionary thought. Mondlane adapted global ideas to African realities, grounding his movement in theory and experience. From 1962 to 1969, he built a philosophical foundation for Mozambique’s liberation — one informed by his education on three continents and his pragmatic grasp of local conditions.

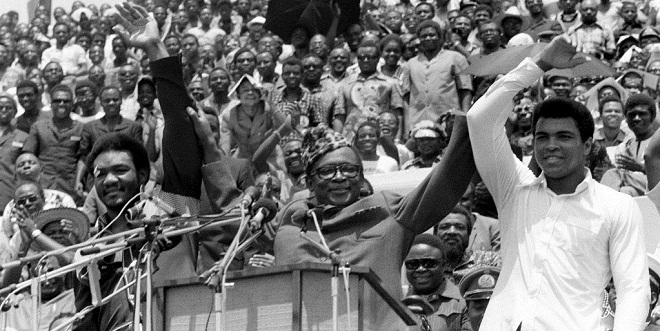

That same year, Uganda and its infamous President Idi Amin Dada hosted the 12th Summit of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). The day before the summit ended, Amin hosted his guests to a lavish reception — a celebration of his marriage to Ms. Sarah Kyolaba — before assuming the OAU chairmanship from Nigeria’s Yakubu Gowon.

Today, the OAU’s successor, the African Union (AU), confronts a different kind of colonisation — the neo-colonialism of aging autocrats and corrupt political systems.

In the Sudans, internal strife has degenerated into war. In Mobutu’s Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, chaos and rebellion reign in the east. In Mozambique, the 2024 elections left a tense calm after Venâncio António Mondlane, an energetic opposition candidate, nearly upset FRELIMO’s long rule in a vote few deemed free or fair.

And in Uganda, our own electoral season unfolds — peaceful, at least for now.

President Yoweri Museveni, leader of the National Resistance Movement Organisation (NRM-O), is expected to extend his 40-year rule. He has co-opted Uganda’s oldest party, the Democratic Party (DP), by appointing its leader, Norbert Mao, as a minister. Once a moral compass in Uganda’s politics, the DP is now reduced to a whisper — content to dine at the table of privilege.

For all Uganda’s achievements under President Museveni, unfortunately, none shines brighter than the extravagance of our political elite.

Last year, Agora Discourse exposed corruption worth billions in the Speaker’s office. In 2023, Parliament was rocked by the iron sheets scandal implicating ministers and MPs alike.

Corruption in the civil service festers under the watch of parliamentary committees that have abdicated their oversight roles.

Corruption remains Uganda’s single greatest threat — the vice that can turn every success into sand.

Mobutu’s billions, like the fortunes of Gaddafi, Bashir, Dos Santos, Bokassa, Abacha, Compaoré, and Bongo, now lie buried with them — useless testaments to borrowed glory. Each believed himself unshakably saddled, yet history has a way of unseating even the proudest riders.

The evolution of a nation cannot be judged from the height of a caparisoned saddle. We learned that in April 1979, forgot it in December 1980, and relearned it in January 1986.

Whether we will need to relearn it again — and at what cost — depends on how long we continue mistaking endurance for destiny, and power for purpose.

*****

By Andrew “Pi” Besi | On X: @BesiAndrew

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price