Why a single remark about future wars rippled through East Africa and what lies beneath the rhetoric

COVER STORY | RONALD MUSOKE | When President Yoweri Museveni warned recently that future wars might erupt over access to the sea, the remark raced through East Africa’s political bloodstream with that familiar cocktail of confusion, alarm, and fascination.

Uganda has always had an anxious relationship with the Indian Ocean; part necessity, part vulnerability, part regional diplomacy, and so, when Museveni suggested that some neighbours “keep changing their stances,” many wondered whether he was signaling deeper geopolitical concerns.

But when one peels back the drama, the reality is much more textured. Uganda, it appears, is not preparing for maritime conflict; rather, it is navigating the messy intersection of international law, regional politics, trade dependency, and presidential frustration. The legal regime governing sea access is clear enough while the political and infrastructural landscape through which that access is negotiated appears less so.

Museveni’s remarks touched Kenyan nerves, but they also touched old truths about colonial borders, the fragility of regional cooperation, and the persistent constraints facing landlocked developing countries. This, according to analysts that spoke to The Independent, is the story behind Museveni’s soundbite.

Country with no coastline and too many worries

Uganda’s uneasy dependence on the Indian Ocean is hardly new. Its trade arteries which bring in goods such as petroleum, electronics, textiles, machinery and pharmaceuticals, all snake through either Kenya’s Northern Corridor or Tanzania’s Central Corridor. Long before East African presidents exchanged cordial press statements and warm handshakes, the colonial railway embedded these connections deep into the region’s economic spine.

Today, freight trucks and pipelines do most of the work. But the political economy of this dependence hasn’t changed. Uganda is a landlocked state navigating a world built for countries with coastlines.

And yet, being landlocked is not unusual. Forty-four countries across the world share the predicament. Some, like Switzerland or Austria, turned geographic disadvantage into global competitiveness. Others, like Rwanda and Kazakhstan, have slowly built resilience and trade efficiency through policy and technology.

What binds them is international law, specifically, Part X of the 43-year-old United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It guarantees landlocked states like Uganda “freedom of transit” to move their goods through coastal neighbours like Kenya. But this guarantee comes with an important footnote: the details must be negotiated, meaning nothing is automatic. It is in that gap between principle and practice that Museveni’s irritation brews.

What “law of the sea” gives and what it doesn’t

A closer reading of UNCLOS shows why Museveni’s lamentation resonates emotionally, but not always legally. Part X outlines three core principles: Landlocked states must be allowed transit to the sea. The terms of that transit must be negotiated by mutual agreement. Coastal states retain full sovereignty over their territory and procedures.

This means Kenya or Tanzania cannot block Uganda’s access outright, but they can negotiate fees, determine procedures, adjust customs systems, modernize pipelines, or alter port policies. They can change regulations, and in democracies, new governments may reset them again.

For legal scholars, this is not a pathway to conflict. “UNCLOS emphasises cooperation,” as one analyst told The Independent. “It is not a basis for militarized confrontation.” In other words, UNCLOS provides assurance but not the insulation from political unpredictability that Museveni seems to desire. And unpredictability, he suggests, is exactly the problem.

Contextualizing Museveni’s remarks

President Museveni’s remarks that ignited this whirlwind came on Nov. 11 at the State Lodge in the eastern city of Mbale during an interaction with the Mt. Elgon-region based journalists. As Javier Silas Omagor, the journalist who moderated the session, later explained to The Independent, Museveni was walking the press through the seven pillars of the NRM manifesto upon which he is seeking a seventh consecutive elective term. The seventh pillar touches East African integration, and that is where Museveni veered into his now-famous riff on borders, oceans, navies, and future wars.

In full rhetorical form, Museveni described Africa’s colonial borders as “irrational” and “restrictive,” lamenting how they trap landlocked states into permanent dependency. “The political organization in Africa is so irrational. Some of the countries have no access to the sea,” he said. “For economic purposes, but for defence purposes, you are stuck. How do I export my products?”

And then he raised the metaphor that launched a thousand headlines and memes across East Africa. East Africa, he said, is like a multi-storey building where only the residents on the ground floor (coastal states) can access the compound. “How can you say the compound belongs only to the flats on the ground floor? The compound belongs to the entire block,” he argued. “This is madness.”

He was even more animated during the verbatim portion of his comments: “In the future we are going to have wars… Because Uganda, even if you wanted to build a navy, how can you build it? We don’t have access to the sea… That ocean belongs to me. Because it is my ocean.” He repeated the word “madness” several times.

But for Omagor, the comment was taken somewhat out of context. Museveni, he told The Independent, was making a structural point — not a threat.

“You see, just like the Egyptians maintain their claim over the River Nile, President Museveni was implying that Uganda shouldn’t be overexploited simply because it does not have direct access to the Indian Ocean,” Omagor told The Independent.

Faruk Kirunda, the Special Presidential Assistant in charge of Press and Mobilization, later offered his own corrective via his X handle. In a widely noted tweet on Nov. 13, he argued that President Museveni’s remarks were about continental strategy, not bilateral sabre-rattling.

“The President was emphasizing the concept of a strategically strong Africa that can defend itself in the four dimensions of land, air, water and space like the advanced nations are doing,” he said.

To Kirunda, Museveni was urging Africans to see resources like oceans as collective continental assets rather than national possessions. “Every African should consider resources like international waters and the continental population as assets that can be used for the collective benefit if we cooperated,” he said.

And he posed a provocative question: “How many know why it’s called ‘Indian’ and not, ‘Chinese’ or ‘African’” ocean? Still, while clarifications from presidential aides help add context, they rarely erase controversy, especially when ocean access is at the heart of long-standing regional political sensitivities.

Why Uganda still needs Kenya (and vice versa)

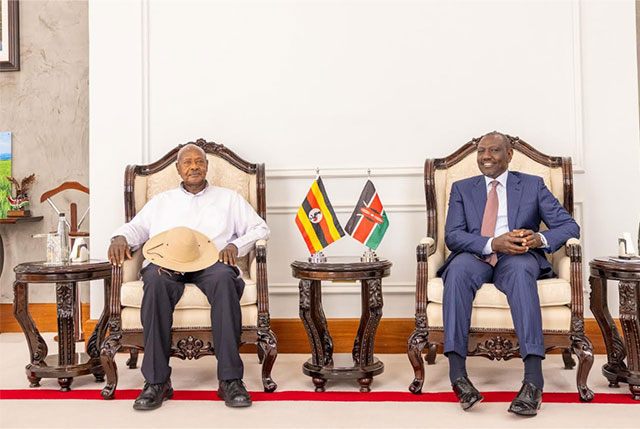

Interestingly, Museveni’s frustration came only months after a highly publicized diplomatic high: his July 30 visit to Nairobi, during which he and President William Ruto signed eight new agreements to deepen cooperation between the two neighbouring states.

Ruto was glowing. “We are united in our commitment to deepening bilateral cooperation and delivering shared prosperity,” he said at State House, Nairobi. The agreements covered tourism, mining, agriculture, fisheries, development of the Greater Busia Metro, quality assurance, livestock, investment promotion — and crucially — transport and logistics.

Ruto spoke of extending the Standard Gauge Railway to Kenya’s western border post of Malaba and eventually into Uganda, and of upgrading major highways into the border region. He even announced a joint plan to establish “the largest steel factory in the region.”

Yet, even with 17 previous agreements and eight new ones layered on top, non-tariff barriers persist. Political transitions in both countries create uncertainty and infrastructure projects move more slowly than diplomatic press statements which is why analysts like Dr. Fred Muhumuza (PhD), a development economist, believe Museveni’s comments were not just about trade.

Dr Muhumuza who lectures economics at Makerere University in Kampala told The Independent that despite the 25 bilateral agreements that exist between the two East African neighbours, it appears President Museveni is referring to something more specific.

“I think he wants guaranteed access to the Indian Ocean irrespective of who is the president of Kenya,” Muhumuza said. Kenya’s democratic system, he added, means leadership often changes hands, and the President may not want to rely on the goodwill of a future Gen-Z leader “who might deny Uganda access to the coast.” In short: treaties are good but irrevocable guarantees are better.

What Kenya actually thinks

Kenya’s official response was calm. Foreign Affairs Cabinet Secretary, Musalia Mudavadi, spoke days later, during a quarterly briefing and stressed that Kenya takes its obligations seriously.

“Kenya is a responsible member of the international community,” he said. “It is in our interest to facilitate any landlocked country that wishes to use the port of Mombasa. And in any case, what would be the value of the port if it does not generate revenue?”

Mudavadi said international law recognizes both the rights of landlocked states and the sovereignty of transit states. Or, as Nairobi-based analyst Gordon K’achola told The Star, the law “does not create a right to sovereign territory on the coast.” He cited the International Court of Justice’s refusal in April 2013 to compel Chile to negotiate sovereign coastal access for Bolivia as a precedent.

If Museveni is hinting at “exclusive footholds” along the coast, K’achola warned, that could be viewed as “territorial encroachment” — precisely the kind of trigger that could cause conflict. Diplomacy, he said, is the safer route.

Ugandan navy on Indian OceanBut can Uganda actually have a navy on the Indian Ocean? Surprisingly, the answer is yes, at least according to Godber Tumushabe, the Associate Director of the Great Lakes Institute for Strategic Studies, a Kampala-based public policy thinktank.

Tumushabe told The Independent that he does not know whether President Museveni knows about the international legal frameworks governing the three so-called global commons (the high seas, the Antarctica and the OutSpace). He says these three global commons are basically spaces which are beyond the territorial jurisdiction of individual states.

In the context of President Museveni’s frustration about accessibility to the Indian Ocean, Tumushabe says that although coastal states have jurisdiction over their contiguous zones (the territorial sea zone and the exclusive economic zones), these states still have limits over the treatment of these zones and there is a lot of flexibility for non-coastal states when it comes to having access to these spaces.

“Uganda can actually have a navy force on the Indian Ocean because it (navy) operates in the high seas,” Tumushabe said. All Uganda would need is to “negotiate docking rights with the Kenyan government,” a task he sees as a matter of diplomacy, not geography.

He added that coastal states have limits over their ocean zones, and the high seas — part of the so-called “global commons” — remain open to non-coastal states. The bigger barrier, he argued, is not law but technology. Uganda would need the capabilities to exploit these provisions meaningfully. “The bottom line is that the international legal system gives a lot of leverage to non-coastal states like Uganda when it comes to access to the global commons,” Tumushabe told The Independent.

Landlocked countries are falling behind

However, Uganda’s frustrations mirror a broader challenge facing landlocked developing countries (LLDCs). The Draft Gaborone Programme of Action for 2024–2034 outlines a grim reality: LLDCs account for just 1.1% of global merchandise exports. They remain heavily dependent on transit neighbours. Their transport infrastructure is underfunded and often fragmented. Their economies lack diversification and remain vulnerable to external shocks.

And even with increased participation in regional agreements — from 3.3 to 4.3 agreements per country — structural constraints persist. The document bluntly notes “little progress” in implementing Part X of UNCLOS. It says transit rights exist on paper, but practice is often undermined by logistical bottlenecks, inconsistent rules, cross-border delays, and governance gaps.

It is precisely these practical frustrations that Jane Nalunga, the Executive Director of the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI), a non-profit that works to promote pro-development trade, fiscal and investment-related policies and processes in Africa, sees in Museveni’s remarks.

She told The Independent that Museveni’s remarks highlight persistent challenges faced by landlocked developing countries and these are issues that were central to the discussions of the Third UN Conference on Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDCs) and Transit Countries which was held in Awaza, Turkmenistan, in August this year.

“Uganda’s experiences reflect broader global concerns regarding the effective implementation of transit agreements, obligations of transit countries, and the need for predictable, efficient access to seaports and international markets,” she said.

Uganda faces “non-tariff barriers, administrative delays, high transport costs, and logistical bottlenecks,” she notes, adding that these challenges have blunted the promise of the EAC’s Customs Union and Common Market.

But Nalunga also quickly added that President Museveni’s concerns also illuminate the intersection between trade, infrastructure, and security, an area that was emphasized at the UN LLDCs Conference that was held in Awaza, Uzbekistan.

“Reliable transport systems, harmonized customs procedures, and coordinated regional infrastructure development remain prerequisites for predictable trade. However, operational gaps, inconsistent application of regional rules, and governance challenges among EAC partner states continue to impede progress.”

“Addressing these issues requires tackling structural and institutional weaknesses, including dispute resolution mechanisms, transport corridor management, stronger political will, regulatory transparency, and harmonization of standards,” Nalunga said, adding that: “Strengthening these areas is essential not only for achieving EAC integration objectives but also for advancing the broader international agenda aimed at improving the trade competitiveness and sustainable development prospects of landlocked countries.”

Could war really break out over access to the sea?

Veteran Ugandan journalist, Charles Onyango-Obbo, offered one of the most striking interpretations. Museveni, he argued on Nov. 15 via his social media platforms (X and LinkedIn), is not wrong about future wars over access to the sea. But if conflict comes, it will likely start in the Horn of Africa, not East Africa. The reason? Ethiopia.

Onyango said Ethiopia is the world’s most populous and largest landlocked country. It is on track to become Africa’s fourth-largest economy in the next 25 years. Historically, Onyango-Obbo noted, there is “no modern precedent for such a country being landlocked.” Its neighbours are small. Ethiopia could “sacrifice 5–10 million people” and “cut a corridor to the sea through Djibouti, Eritrea or Somalia.”

Somaliland is already signaling it might exchange coastal access for diplomatic recognition, he said. East Africa, in contrast, is the reverse. The smaller states; Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, are the land locked ones. Kenya and Tanzania are larger, coastal, and interconnected with their neighbours through the East African Community framework.

Onyango argued that although Uganda’s army may rival Kenya’s, the economies differ substantially. And the region’s political culture — for all its quarrels — still leans toward negotiation.

The diplomatic logic

Moses Owiny, the Founder and Chief Executive of the Centre for Multilateral Affairs, a Kampala-based thinktank, captured the diplomatic reality succinctly. “I think Museveni’s statement indeed may imply a threat or declaration to use force,” he said. “However… most of the regional conflicts or tensions between Kenya and Uganda have not escalated always but rather resolved diplomatically.”

He sees Museveni’s remarks as part of a broader argument for equitable sharing of regional resources — not a destabilizing move. “At the moment,” he added, “I don’t see how his statement has a negative bearing on trade within the region.”

So, what did Museveni actually mean?

Strip away the metaphors, the emotion, the campaign setting, and the rhetorical flair, and Museveni’s message boils down to three themes: Structural vulnerability where Uganda depends on its neighbours for sea access while in terms of strategic anxiety, Museveni also dislikes this dependence and wants long-term guarantees. As for his continental ambition, he continues to envision an Africa capable of competing with global powers — on land, air, sea, and even space.

His language might have been dramatic and his frustration was clear but his underlying concern is neither new nor unfounded. Uganda’s access to the Indian Ocean depends not on UNCLOS, but on the politics of Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, politics that shift with every election.

That is why, even as he chides Kenya for “changing leaders,” he continues to sign agreements. That is why, even as he warns of future wars, he champions integration. And that is why his remarks struck a chord. They exposed a truth every landlocked country knows: having rights on paper does not always translate into security in practice.

Museveni’s remarks were loud, colourful, and easy to sensationalize. But the story they reveal is quieter, more sober, and much more regional in nature. Uganda is not marching toward maritime conflict. Kenya is not withholding access. Tanzania is not posturing. The EAC is not on the brink.

But Uganda is confronting its long-standing vulnerabilities. And the region is being forced, once again, to reckon with the unfinished business of colonial borders, regional infrastructure, and the slow work of integration.

If anything, Museveni’s outburst may have done the region a favour. It re-opened a conversation East Africa keeps deferring: how to build a system where access to the ocean, the literal gateway to global trade, is predictable, stable, and insulated from political winds. For all his metaphors about buildings and compounds and “madness,” Museveni asked a question the region cannot ignore: If the compound belongs to the whole block, why does it feel like some residents still worry about being kept outside the gate?

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price