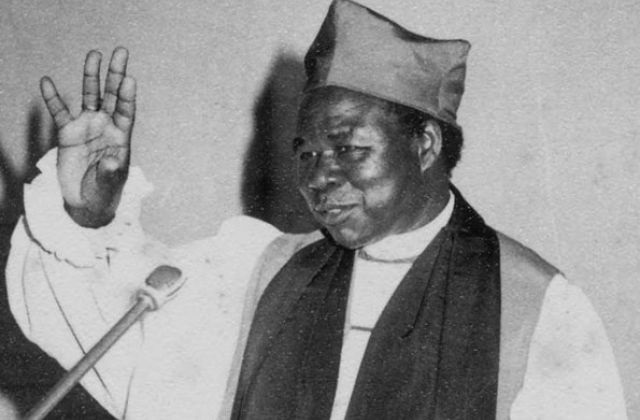

COMMENT | REGINA ASINDE | On this public holiday, Uganda pauses to remember Janani Luwum, the Archbishop who paid with his life in 1977 after confronting the brutal regime of Idi Amin. His death was not an accident of history. It was the consequence of moral courage. He spoke against arbitrary arrests, torture, and state violence. He documented abuses. He protested formally. And he refused to baptize injustice with silence.

Nearly five decades later, we gather in cathedrals to honour him. But remembrance without reflection risks becoming ritual. The uncomfortable question remains: has the Church he led preserved his courage, or merely his memory?

Across the country today, prayer services are being held in his honour. Yet in recent years, many religious institutions have appeared hesitant to challenge contemporary injustices with the same clarity. Political leaders accused of corruption, electoral malpractice, or abuse of office are often welcomed into places of honour. Thanksgiving services are organized. Generous donations are received. Public prayers are offered for their continued success. Meanwhile, the very issues Luwum confronted—impunity, fear, misuse of state power—persist in different forms.

This is not to deny that the Church prays for all leaders, as Scripture instructs. Prayer for those in authority is biblical. But prayer without accountability is incomplete. When the prophetic voice grows quiet in the presence of power, something essential is lost.

The Church has historically been described as the conscience of the nation. A conscience does not flatter; it convicts. It does not seek proximity to power; it speaks truth to it. The tension arises when institutions become dependent—financially or socially—on the very leaders they are meant to hold accountable. Cathedrals are expensive to build. Programs require funding. Political favour offers protection and influence. Yet every form of dependency comes at a cost.

Some argue that every leader is from God and therefore deserves honour. That is true in one sense: no authority exists outside divine permission. But biblical history is equally clear that not every ruler is a blessing. Some are instruments of judgment. The prophetic responsibility of the Church is not to sanctify power automatically, but to measure it against justice, righteousness, and mercy.

Courage is costly. Luwum’s witness reminds us that speaking against injustice carries real consequences. The political climate of the 1970s was brutal. Today’s context is different, but not without risk. It may be easier for institutions to preserve stability than to provoke confrontation. Yet if the Church loses its moral clarity, it risks becoming a ceremonial accessory to power rather than a guardian of truth.

Honouring Luwum demands more than wreaths and sermons. It demands introspection. Are we content with symbolic remembrance, or are we willing to recover the prophetic edge he embodied? The Church need not become partisan. It must, however, remain principled. Justice cannot be outsourced to politicians. Integrity cannot be negotiated for access.

A nation is strengthened when its religious institutions are neither adversarial nor compliant, but courageously faithful. As we commemorate a martyr, we must ask whether his example challenges us—or merely comforts us. Memory should disturb us enough to act.

The author is the Country Director of LERWA–Land and Environmental Rights Watch Africa Ltd, an author, and a community organiser with experience in human rights advocacy. Email: skasede@gmail.com

The author is the Country Director of LERWA–Land and Environmental Rights Watch Africa Ltd, an author, and a community organiser with experience in human rights advocacy. Email: skasede@gmail.com The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price