Witch-hunt or nemesis?

It is not the first time the youthful lawyer has taken on the Chief Justice. On Aug.21, last year, Male Mabirizi petitioned Rebecca Kadaga, the Speaker of Parliament against the approval of Owiny-Dollo as Chief Justice.

Mabirizi accused Owiny-Dollo of being “incompetent, engaging in acts of misbehaviour and/or misconduct.”

“I am aware that the president has nominated Justice A.C Owiny-Dollo for approval as Chief Justice and the purpose of this letter is to object to the nomination and any approval because his past conduct puts him below the standards set by article 144 (2) (b) and (c) of the Constitution.”

Mabirizi also accused Owiny-Dollo who was then Deputy Chief Justice of turning the Constitutional Court a no-go area for people not represented by advocates. “He discriminates self-representing litigants and uses scare tactics towards parties demanding for their rights in court.”

Mabirizi said he had tasted Owiny-Dollo’s wrath on 9th April 2018 at Mbale in his Constitutional Petition No.49 of 2017, Male H. Mabirizi K. Kiwanuka v Attorney General when “he, with threats to throw me out, evicted me from court seats my only crime being self-represented.”

“He threw me to the dock as if I was standing criminal trial and when I protested, he said that his court was not going to be the first court to breach rules of fair hearing,” Mabirizi said.

“He later prevented me from cross-examining Gen. David Muhoozi, the Chief of Defence Forces and helped him answering my questions and threatened to throw me out. The only reason he denied me Shs 20 million costs was because I was self-represented.”

“A.C Owiny Dollo is so incompetent that even when the court he chaired promised to give detailed reasons why the Speaker was summoned, up to date, none was given and I am not aware why the Speaker was not summoned as I applied,” Mabirizi said, adding that approving A.C Owiny-Dollo then, would be disastrous to the administration of Justice.

When to recuse

In a blog written on Oct.28, last year, by Louis J. Virelli III, a professor of law at Stetson University College of Law in the U. S, he noted that recusal or the act of a specific judge being removed from a specific case, usually for ethical reasons, is an old practice.

Virelli, who wrote the blog for the American Constitution Society, said the practice reflects a concern about self-interested judging that is at odds with the impartial, independent judiciary envisioned by a jurisdiction’s constitution and, to that end, serves two general purposes.

“The first is to protect individual litigants from biased judges. Our judicial system cannot function if litigants lack a fair opportunity to present their cases to an open-minded arbiter,” Virelli said.

“The second is to protect the integrity of the judiciary, which is necessary to maintain public confidence in the judicial institutions and actors.”

Virelli says Supreme Court recusal is important to the confirmation process for at least three reasons. First, because Supreme Court justices’ recusal decisions are unreviewable and very rarely explained, the confirmation process may be the best opportunity for public vetting of a justice’s views on recusal.

It is perhaps, he added, the only chance for public inquiry into how the prospective justice envisions balancing the institutional cost of recusal against the benefits of protecting the integrity of the Court from real or perceived bias. Second, a prospective justice may invoke future recusal problems as a reason not to answer a question at their hearing.

Third, and relatedly, because Supreme Court justices rarely, if ever, publicly answer questions about their personal views on the law or judging (let alone under oath), confirmation hearings are among the very few instances where a justice may publicly take a position that could be grounds for recusal in a future case or cases.

Virelli explained that from the Bush v. Gore case, the public is inherently skeptical about the Court’s involvement in a presidential election, especially one that appears to be decided along party lines.

EAC Supreme Court

Mabirizi’s petition has again brought to the fore the contentious issue of how best to handle high-stakes petitions that often end up in the Supreme Court, where judges are all appointed by the president.

Over the past decade, presidential elections have been challenged in courts in Kenya, Ghana, Gabon, Zambia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Malawi and Zimbabwe.

But except Kenya and more recently Malawi where elections were nullified, judiciaries in each of the countries have often decided in favour of the status quo with many cases being dismissed without fair consideration of the merits of the petitions. In the case of Uganda, the political implications for security, peace and stability were reportedly deemed to be too critical for the Supreme Court judges to rule otherwise.

Retired Tanzanian Supreme Court judge, Eusebia Munuo and Ugandan law scholars Prof. Fredrick Ssempebwa, Dr. Businge Kabumba and Justice Prof. Lilian Tibatemwa Ekirikubinza in their book titled, “A Comparative Review of Presidential Election Court Decisions in East Africa,” noted that for independence of the judiciary to hold in such tensed-up circumstances as a presidential election petition, contesting political forces must have a bare minimum level of balance with no overbearing party controlling all the institutions.

During a public lecture in 2017, Justice Remmy Kasule of the Uganda Constitutional Court suggested that it is high time the East African Community created a Supreme Court whose decisions on fractious issues like presidential election petitions are binding in each of the six member states. He said this would cure the region’s supreme courts of accusations of bias in tense cases such as witnessed in the Kenya presidential election petition in 2017.

The Kenyan Supreme Court directive of Sept.01 2017 compelled the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) to hold fresh elections within 60 days. But it also rattled the Kenyan incumbent President Uhuru who had been declared winner by the IEBC after winning by 54.27% of the vote against Raila Odinga’s 44.74% of the vote.

However, fresh elections on Oct.26 were won by Kenyatta with 98% of the votes cast after Odinga rallied his supporters to boycott the re-run. When Kenyatta was declared winner by the IEBC, the opposition again challenged the result in the Supreme Court. But on Nov.20, the Supreme Court upheld Kenyatta’s win, clearing the way for Kenyatta’s swearing in on Nov.28.

As such, Justice Kasule appeared to be searching for a fair and transparent redress mechanism that is unencumbered by national consideration.

The assumption is that the decision of a regional court would command the respect of the people and, therefore, lend legitimacy and credibility to the election and serve as a possible mitigation to violent post-election response. Justice Kasule said creating a legally binding supra-national Supreme Court for East Africa would be the answer to creating sanity within East Africa.

“If we are to make East Africa strong, let us begin to act as East Africans where we can put our act together and push the positive values that can push us forward,” Kasule said, “If there is a matter arising in each of the member states, then the court would choose members from each of those benches to handle the contentious cases.”

Kasule said this kind of jurisprudence would go a long way in addressing the needs of each and every East African citizen. But, Dr. Willy Mutunga, the former Kenyan Chief Justice who was in Kampala at the time to deliver the fourth ACME lecture on media and politics in Africa, agreed with Justice Kasule, only to an extent.

Mutunga said, for this court to work, it would be very ideal where judges from say, Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania preside over a presidential petition in Uganda and those in Uganda, Kenya and South Sudan hear a petition from Burundi.

This, he said, would lessen the perspective of “this judge was bribed.” But Mutunga was quick to add that this kind of structure would also get stuck at some point considering that East Africans are quite closely related (ethnically and networked).

Still, he said, a structure that handles presidential petitions and other political decisions that tend to dent the image of the national judiciaries is worth trying. But critics of this model noted that outside an East African political federation, it would be difficult for the EAC states to give up their sovereignty.

For now, Ugandans await the Supreme Court’s decision on whether or not Chief Justice Owiny-Dollo will recuse himself from the case before him for purpose of instilling confidence in the country’s highest court.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

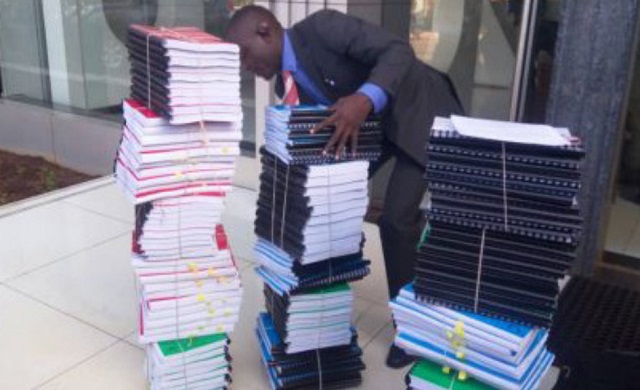

Update: On Feb.19, Chief Justice Owiny-Dollo noted that he has the conviction that what he is doing is right (and) whatever is being said outside court premises has no bearing on the presidential election petition. “The judges took oaths to protect the Constitution. In the oath, we all took to exercise judicial functions entrusted to me in accordance with the laws of Uganda without fear, favour, affection or ill-will.” He added: “We are not opposed to fair criticism but criticise my conduct and decision…Speaking against me without a chance to respond is cowardly. You can choose to malign us a thousand times but if you have an issue and come before me, I would proceed in line with the law.” Owiny-Dollo was speaking during the hearing of an application in which Kyagulanyi was seeking for permission from the Supreme Court to allow him file an additional 200 affidavits to support his petition challenging the victory of Yoweri Museveni in the just concluded presidential elections. In an 8-1 ruling, the Supreme Court dismissed Kyagulanyi’s request.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price