Gaps in Uganda’s digital ID rollout could exclude people with disabilities from critical public services

SPECIAL REPORT | RONALD MUSOKE | When on Feb. 9, Claire Ollama, the friendly and polyglottic Registrar of the National Identification and Registration Authority (NIRA), declared the nationwide digital ID registration and renewal exercise “successfully concluded,” the numbers seemed to tell a story of triumph.

Ollama said over the last eight months, over 35 million Ugandans have been uniquely identified, millions of records migrated from the old system onto a new one, and millions of new or renewed IDs printed. By official accounts, nearly 90% of the renewal target and millions in mass enrolment has been achieved.

“We have successfully migrated all data from the old system into the new one and I wish to inform you that 28,571,893 are now migrated into the new system…Every record that we did have in the old system is now present in the new system,” Ollama said during a joint security weekly press briefing at the Police headquarters in Naguru, a Kampala suburb.

Ollama added that, in regard to renewals, changes of particulars and offering first IDs for people that had a National Identification Number (NIN), NIRA was looking at a target of 15.8 million and it achieved 14,311,877, a performance of 90.5%.

“We were also supposed to enrol 17.2 million Ugandans, majority of these were children, minors who do not access service of their own accord…The ability to access service was totally dependent on an adult, a caretaker, a benefactor or a parent. And as we have always engaged that there was a bit of sluggishness in this area, it is painful to report that we have only managed 37.3% to this end.”

In terms of printery of the digital cards, Ollama said that the printing process is a function of people that qualify for a card. “Printery is a function of the idea that someone needs to qualify for a card to get it. So not everyone who is enroled qualifies for a card. And therefore the target for our printery is a function of processed data that now is ready to culminate into a card,” she said. Ollama noted that by the close of business on Feb. 8, NIRA had achieved 10,152,559, which is commendable to the extent that it had 14 million of the people that were card related.

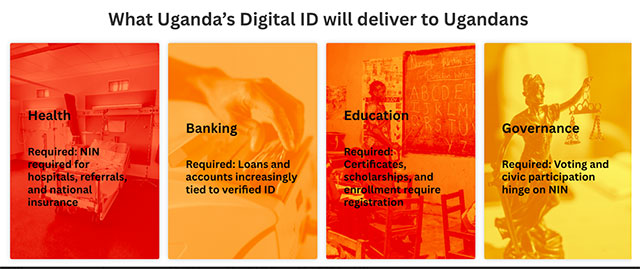

The NIRA spokesperson, Osborne Mushabe, appearing two days later (Feb.11) on the local broadcaster, NTV’s MorningatNTV segment, emphasized the importance of the digital ID registration, noting that the ID will be a requirement for access to government services, healthcare, education, and banking.

“Not every person living in Uganda is a Ugandan. So, the moment we register you and assign you that unique number, you are able to access services as a citizen,” he said. “This country belongs to all of us.We don’t want anyone to suffer while accessing government services.” Mushabe said although the mass exercise has ended, NIRA’s offices across 146 districts remain open for routine registration and renewals.

But, behind all these statistics lies a gap that numbers cannot capture. For many Ugandans living on the margins, particularly persons with disabilities and those with mental health challenges, the promise of inclusion remains unfulfilled.

Confined to homes, institutions, or remote villages, these citizens are often invisible to the very systems meant to count them. While NIRA acknowledged missing some targets due to deaths or migration, the structural and logistical barriers faced by vulnerable populations received little attention.

A system built for the able-bodied

Uganda’s digital identity system is framed as transformational; a gateway to healthcare, civic participation, education, finance, and social protection. But disability advocates ask a difficult question: what does universality mean when people living with disabilities cannot queue, cannot speak, cannot sign, cannot travel, or cannot consent?

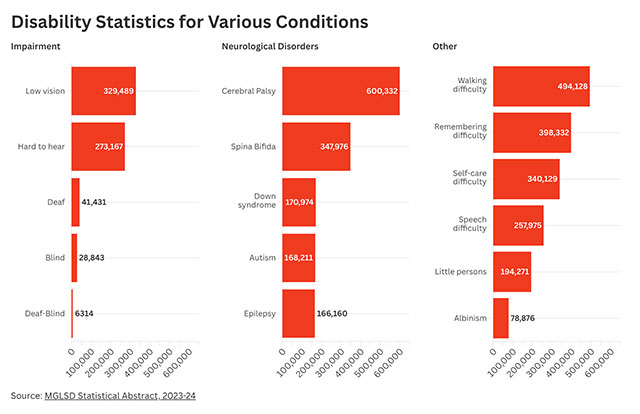

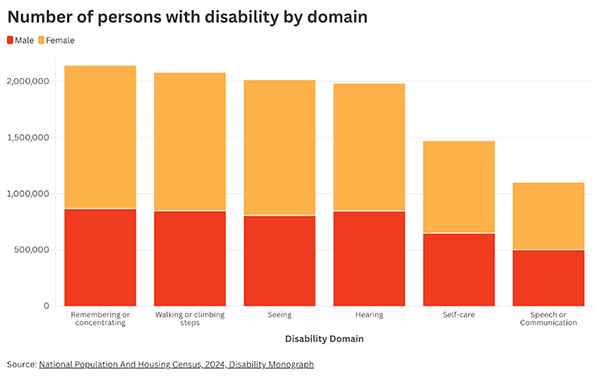

Across the country, there are hundreds of thousands of citizens with mobility challenges, memory impairments, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and intellectual disabilities. The Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development’s Statistical Abstract 2023/2024 put the disability prevalence at 3.4 % among Ugandans aged five years and above. This is about 1.29 million people. Other datasets place the figure higher. The Disability Monograph 2024 published by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) in July, last year, reported disability prevalence at 13.2% among people aged two and above, rising to nearly 47% among those over 60.

Interestingly, in an attempt to account for the people NIRA failed to reach, Ollama said, it is possible that the 10% gap “could relate to people that maybe are deceased.” “It is also possible that human beings are not rigid; they are mobile and could have moved to other areas, which could inform their inability to access service,” she said. In her 38-minute address of the media at the police headquarters, Ollama did not admit NIRA’s difficulty in reaching Ugandans living with disabilities.

Invisible citizens

Weeks earlier, The Independent had reached out to Rosemary Kisembo, the NIRA Executive Director to verify how the agency was handling registration of a special group of citizens in the communities – the disabled including those commonly described as “mad.”

In a short telephone interview on Jan.13, she said: “The Constitution (of Uganda) is very clear. “As long as one’s mother or father is Ugandan or whether the grandmother/grandfather is Ugandan, the person is eligible to be registered for a National ID. “As long as you belong to the 64 tribes of Uganda, the individual must be registered,” she said. As for the people described as “mad,”Kisembo told The Independent that as long as the community can identify the individual, we register them… it does not matter whether they are lame, deaf, blind, or mute.”

She pointed to Schedule III of the Disabilities Act 2020. She said NIRA has worked with various authorities including; the National Council for Persons with Disabilities and the National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda (NUDIPU) during the entire ID registration. “It’s not an issue for us,” she told The Independent. “As long as you meet the criteria for registration, the rest is a detail.”

But an investigation by The Independent reveals a different reality. On the same day we spoke to Kisembo, we visited Kireka Home for Children with Special Needs which is about 7km on the eastern outskirts of Kampala City. This is a government-affiliated institution and it’s both a home and school for children with special needs.

Inside the gated compound, we found a woman, who the caretaker later told us was 68 years old. She was pushing a wheelchair back and forth under the mild early afternoon sun. Despite NIRA going into the seventh month of the nationwide ID registration and renewal exercise, the woman who is incoherent in her speech had no knowledge of the NIN system, or that access to healthcare, education, and social protection is increasingly tied to this digital card.

The home, which has operated for over 30 years, currently houses seven residents ranging from those aged between 8-70 years, all of whom live there permanently. In addition, about 120 children with similar conditions from surrounding communities attend the school each day during the school term. Many residents cannot stand for long, communicate verbally, or move independently.

“We have not been able to take these people to the main registration centres.They have therefore never been registered,” a staffer at the special needs home, who prefered to remain annonymous, told The Independent, citing understaffing.

In Kikaya B village, near the Bahai Temple in Kampala’s Kawempe Division, The Independent met 45-year-old Loy Mukyeyaya through her tutor, Judith Andinda. Mukyeyaya has been unable to obtain a national ID for ten years, despite the government introducing the document in that time. She is mute, left school in Primary Seven, and does not use formal sign language. It was only recently that volunteers from the Jehovah’s Witnesses began teaching her basic communication skills—through which she learned that she is entitled to a digital national ID.

With the tutor’s help, she was able to visit the nearby NIRA offices in Ntinda and received assistance filling out the application forms. But, by the time NIRA announced the end of the mass ID registration exercise on Feb. 9, she and her tutors had been unable to secure the required endorsement from the Local Council chairperson.

To make the situation even worse, there were no interpretors at the registration centre, and Mukyeyaya had to rely on her tutor to answer questions on her behalf. “She has no phone and she has limited reading skills. Without help, she cannot navigate this process,” Andinda told The Independent, adding that she encounters many others like her in the communities she often visits during her evangelical work.

Inside the village for the blind

In Luubu A village in the Southeastern district of Mayuge, about 120km from Kampala, The Independent met about 40 blind adults who live in a settlement dating back to the 1950s. People in this community have lived together since colonial times on land donated by Busoga Kingdom. They farm, rear chickens, and make cane-chairs. They have even formed a community-based organisation called Twezimbe Luubu Group of the Blind.

When we sat down to talk, their chairman Moses Mugabe and vice chairman Charles Muyingo described long, exhausting journeys to parish centres to register for the national ID. “For able-bodied people, three kilometres is nothing,” Muyingo told The Independent on Jan. 25. “For us, it is far.”

Mugabe described the struggle to access the ID registration venues: “Our community gives us strength but when it comes to ID registration, we feel left behind. It is not just a card—it is our access to the services we deserve as citizens.”

For residents like Harriet Mutesi, a blind member of the group, traveling even three kilometres to a parish registration centre is a major challenge. Escorts or assistants, often children, are required; yet the long and winding registration sessions may coincide with school terms, adding further complications. “Even when we arrive, we sometimes feel ignored because we are blind,” she said.

On the days The Independent visited various NIRA registration centres in Kampala including Ntinda, Kawempe and Kireka, we did not see any special desks or structured priority systems in place for persons with disabilities and people with mental health challenges.

Ali Ddumba, the director of the Kireka Persons with Disability Development Initiative (KPDDI), expressed frustration with NIRA’s failure to establish a special desk for people living with disabilities. “Who registers that mute man you see there?” Ddumba asked, gesturing toward a tall, energetic man in the community known to be unable to speak. “Who registers children with special needs? Out of every hundred people with disabilities, perhaps only 30 are registered—the ones mobile enough to reach the centres.”

Francis Mutebi, a newly elected Councillor for persons with disabilities in Namugongo Division in Wakiso District told The Independent that many of his members remain unregistered. “They are in their homes, most are immobile and they need boda bodas (motorcycle taxis) to move. The deaf go to centres and receive no help. No interpreters. They don’t know what to do,” he said. “Now when government programmes require the new ID, these people will miss out. That is double jeopardy.”

Ddumba told The Independent that he believes many people with disabilities in the communities were systematically being excluded. “If government is building a database but leaving out a category of citizens,then planning for these people is dead on arrival.”

NIRA’s response

The Independent reached out to NIRA’s executive director again, seeking answers to the concerns from the communities we had visited. At a short meeting with Rosemary Kisembo at Kololo Independence Grounds, assurances were given that the Authority had established systems to accommodate vulnerable populations. A subsequent formal inquiry raised specific questions about how NIRA handles applicants with physical, sensory, and psychological disabilities, particularly in cases involving impaired consent, disorientation, or mobility challenges.

The Independent’s inquiry referenced NIRA’s May 14, 2025 press statement, which acknowledged special consideration for groups such as the elderly, the sick, persons with disabilities confined at home, and expectant mothers. However, we questioned why people with mental illness were not explicitly mentioned, and sought clarification on protocols for enrolling applicants who cannot sit still, communicate clearly, or independently provide consent. Additional concerns centered on accessibility at parish registration centres, reliance on strangers for form-filling, and the lack of publicly available data on how many persons with disabilities (PWDs) had been registered so far compared to census estimates.

In its written response, NIRA emphasized that its mass enrollment exercise is guided by a “No Ugandan Left Behind” principle and supported by the transition to the Modular Open-Source Identity Platform (MOSIP), which it described as a foundation for universal inclusion. The Authority stated that its approach aligns with Uganda’s legal framework, defining disability broadly to include physical, mental, sensory, and psychosocial impairments that significantly affect daily functioning.

NIRA explained that where individuals are unable to apply for registration due to illness or mental incapacity, responsibility legally falls to guardians or caregivers. “Enrollment officers are trained to work with these caregivers and may rely on verification from Local Council leaders to confirm identity details. Officers are instructed to act with patience and discretion, ensuring the process remains lawful, humane, and dignified,” NIRA said in its statement.

The Authority highlighted extensive collaboration with the National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda (NUDIPU), the National Council for Persons with Disabilities, and the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, the ministry responsible for people with disabilities. According to NIRA, these partnerships informed its outreach strategies, operational procedures, and communication methods, helping tailor services to the lived realities of PWDs. This engagement also led to a memorandum of understanding and specialized inclusivity training for NIRA’s top management, embedding disability awareness into institutional culture.

Inclusivity extended to recruitment, NIRA said, adding that during mass enrollment exercise, NIRA introduced affirmative-action quotas for persons with disabilities, including visually impaired applicants, aiming to ensure field teams reflected national diversity and brought lived experience into service delivery.

NIRA added that it had “established priority registration zones—known as Zone A—at parish centres for PWDs, older persons under the SAGE programme, and pregnant women, reducing wait times and physical strain. Mobile registration kits were deployed to reach individuals unable to travel, enabling home-based enrollment supported by village-level identification and mobilization through Local Council structures.

To address biometric challenges, “NIRA had adopted a multi-modal identification system.” “In addition to fingerprints, iris recognition is now used for applicants with hand or finger impairments, while facial recognition serves as a fallback when neither fingerprints nor iris scans are feasible.”

In such cases, NIRA said exception records allow enrollment using facial biometrics combined with verified biographical data and local authority confirmation, ensuring applicants are not excluded due to physical limitations. The Authority also mandated staff to assist PWDs with form completion, working closely with caregivers to protect accuracy and confidentiality. By decentralizing services to more than 10,000 parishes nationwide, NIRA said it significantly reduced travel barriers for people with limited mobility.

These efforts, NIRA noted, were recognized in 2025 when the Authority received the Disability Inclusive Employer of the Year award at the Mr. & Miss Ability Uganda ceremony in Kampala—a public acknowledgment of its attempts to create a more accessible registration system. While challenges remain on the ground, NIRA maintains that its evolving framework seeks to ensure every eligible Ugandan, regardless of ability, can be counted and documented.

A different reality on the ground

Yet the tension between policy and lived reality remains. Take the experience of Dr. Abdul Busuulwa, a disability studies lecturer at Kyambogo University who is educated up to PhD level. Dr Busuulawa told The Independent that he too, has encountered barriers while trying to renew his national ID.

He referred the ID registration and renewal process as a lifeline for persons with disabilities yet it is one that remains riddled with structural gaps. Busuulwa challenged assumptions embedded in the process itself, particularly around literacy and consent. Registration forms, he noted, often label applicants as “unable to sign,” a designation that can wrongly imply illiteracy or incompetence. For many people with disabilities, a thumbprint functions perfectly well as a signature. The problem is not capability, he argued, but inflexible systems that fail to recognise alternative ways of participation.

During his own attempt to renew his ID at a centre in Mpererwe in the northern reaches of Kampala, a long queue and dismissive staff left him discouraged enough to walk away. For someone with professional standing and institutional knowledge, the experience was demoralising. For poorer, less connected Ugandans with disabilities, he suggests, it is often insurmountable.

Busuulwa points out that Uganda’s disability law recognises a wide spectrum of impairments—visual, physical, intellectual, psychosocial, hearing, deaf-blind, and multiple disabilities—each presenting distinct registration challenges. Applicants with cognitive or psychosocial disabilities frequently require caregivers to assist with questions and consent, adding logistical and financial burdens to an already difficult process.

While NIRA’s frameworks and partnerships demonstrate intent and capacity, the human stories from Kireka Home, Luubu A village, and Kikaya B in Kawempe Division reveal the gap between policy and practice, highlighting the urgent need for proactive, accessible, and context-sensitive registration measures.

John Chris Ninsiima, the Director of Programmes at the National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda (NUDIPU) told The Independent that the push for inclusivity in the national identification process is deeply personal.

As he explained to The Independent on Jan. 23, NUDIPU has spent the last 38 years advocating for the rights of persons with disabilities, striving to ensure their full participation in society—across public administration, health, education, media, and national development.

“Our mandate is to make sure persons with disabilities enjoy total inclusion,” Ninsiima said, emphasizing that access to national identification documents is central to this mission. “We are equally interested in ensuring that our persons with disabilities have equal access to national IDs, like any other person.”

Yet, in practice, many face barriers. “Accessibility challenges remain,” Ninsiima noted. “Sometimes it’s the unawareness, sometimes it’s the attitude, and sometimes it’s just the difficulty of reaching registration centres.”

The technical requirements of NIRA’s registration process present unique obstacles. Thumbprints, iris scans, and facial recognition—common identifiers—can be inaccessible for many. “For example, some of our members don’t have hands,” Ninsiima explained. “Some don’t have eyes or functional irises. Our main point has been to advocate for alternative identifiers for those who don’t have these body parts.”

Despite the challenges, there are encouraging signs. During the recent rollout for national IDs, NUDIPU coordinated directly with NIRA to establish a registration centre at their headquarters. This allowed members from nearby communities in Kampala to access registration and renewal services conveniently. “That gesture by NIRA was important,” Ninsiima said. “It sent a clear message that persons with disabilities should also have IDs and that their rights are being recognized.”

But NUDIPU’s network spans 17 national disability organizations, covering physical impairments, hearing impairments, albinism, and other categories, as well as district-level unions in every municipality. Through this network, Ninsiima and his colleagues mobilize members to ensure they are counted in national processes. He told The Independent that many still miss out due to distance, lack of information, or financial constraints.

“The National ID is an entry point for government services,” he emphasized. “Those who do not have it—even persons with disabilities—may miss out on critical initiatives, whether in healthcare, banking, or social programmes. It is their right to access registration like any other Ugandan.” He says both civil society and government authorities must intensify efforts, ensuring every person, regardless of ability, is reached. “The LC structures can help make sure each person in their locality—including persons with disabilities—has a National ID. This is about inclusion, about making sure no one is left behind.”

Special needs programme

Robert Offiti, the Regional Manager at the Coalition for Health Promotion and Social Development (HEPS-Uganda), a Kampala-based civil society organization, told The Independent that there’s need for the creation of specialised NIRA teams that are trained in sign language and braille, alongside mobile outreach units dedicated specifically to persons with disabilities.

He also calls for the establishment of a permanent disability-focused unit within NIRA’s structure. “I wish they would take this opportunity to establish a unit for sign language and integrate it into civil registration and vital statistics,” he said. “Such that equity can also be seen in their staffing.”

He acknowledges NIRA’s staffing constraints—previously operating at about 50% capacity—but urges the Authority to use the momentum of current campaigns to institutionalise inclusive practices before funding declines again.

“You don’t want to disadvantage people who are already on the margins,” he said. “Because the ID, the biometrics, the NIN—that’s what will be used to access services.” He adds that future policies, including the anticipated National Health Insurance scheme, could unintentionally lock out people with disabilities who lack NINs, simply because no one took the time to register them.

“These are categories of people who don’t have NINs because, in the first place, no one has been patient enough to take their details and register them in the system,” Offiti said.

Calling for transparency, he urges NIRA to publish disaggregated data showing how many persons with disabilities—by gender and region—have been registered so far, and to use that information to guide targeted outreach. “Messages have to go out clearly to people living with disabilities,” Offiti said. “They need to feel that government cares for them, that they matter in the development agenda—not only at election time, but in their day-to-day lives. And it starts with registration.”

Digital ID is far beyond paperwork

Moses Talibita, a human rights advocate and law lecturer at Nkumba University, told The Independent that the national identification registration exercise is far more than paperwork; it is about dignity, belonging, and ensuring that no Ugandan is left behind.

Talibita, who has long championed inclusivity, told The Independent that registration should reach every citizen, including those living with mental illness, homelessness, or social rejection. “We should create safe communities that embrace everyone—whether it is in digital spaces, accessing digital platforms, or in their right to be registered.”

He says there’s need to mobilize communities to embrace full civil registration, from birth to certification. He says theres’s no single section of the law whatsoever that excludes any person including persons with any mental illness. “The challenge is the practice,” he said.

He also calls upon NIRA to adopt special protocols for registering adults with mental health challenges—similar to arrangements already in place for children and the elderly—allowing relatives or caregivers to escort them and verify their information.“Their challenges should be leveraged on, just like we do for children below 18 or the elderly…We are now in a digital information age, and any person who is not with a national identification number is excluded.”

He also frames the digital ID registration as a fundamental human right, citing international protocols that protect every person’s right to legal identity. Without documentation, he says, individuals risk becoming stateless in their own country—unable to prove who they are or access lifesaving care.

“Mental health does not mean one ceases to be a citizen,” Talibita insists. “These are patients. These are taxpayers. These are Ugandans.” He says as Uganda pushes towards a fully digitized identity system, the progress must be inclusive. “We cannot be part of a community that promotes exclusion just because of a person’s mental illness,” he says. “Registration is their right. It is a universal right.”

Dr. Hafsa Lukwata Ssentongo, the Assistant Commissioner for Mental Health and Control of Substance Abuse at the Ministry of Health, highlights another gap: misconceptions about mental illness often prevent inclusion.

“People think that a person who is ‘mad’ will beat you or stone you. They do not just stone people. There is a reason why they act the way they do,” she said, emphasizing patience and “reasonable accommodation” as key to inclusion.

Dr. Lukwata said “Many people also misunderstand people with mental disorders. They imagine people are stupid or they don’t understand anything. And yet, most of those people can understand, and really know what is going on.”

She told The Independent that individuals with mild conditions are often fully functional and capable of participating in registration processes. “They know their parents. They know their caretakers. They know why they are in that place, wherever they are. And they even have reason why they left home, for those that are just moving around,” she said.

“NIRA needs to have reasonable accommodation for people with mental disorder; they should find alternative ways of getting their information and ensuring that they are also registered, instead of just rejecting or ignoring them.”

For Dr Busuulwa, mass ID enrollment campaigns, if not deliberately inclusive, risk leaving behind precisely those they are meant to serve. “Once the exercise ends, those who failed to navigate queues, distances, or hostile environments are simply erased from the system and for persons with disabilities, the consequences are profound.”

His call is straightforward: registration must be accessible, flexible, and humane. Exclusion, he insists, should never be the default. If someone remains unregistered, it should be by choice—not because the system made participation impossible. “If you are not to be registered, let it be your choice but whenever you want it, there should be enablers for you to be registered within the national registration exercise,” Dr Busuulwa said.

******

*This story has been published as part of the Collaboration on ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa’s (CIPESA) Digital Public Infrastructure Journalism Fellowship for Journalists in Eastern Africa

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price