The latest vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, is a product of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford

Kampala, Uganda | THE INDEPENDENT | The World Health Organisation (WHO) has recommended a new, inexpensive malaria vaccine to prevent malaria in children that can be produced on a massive scale.

The latest vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, is a product of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and the Serum Institute of India.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO director-general, while making the announcement on Oct.02 that doses will cost between U.S. $2 and U.S. $4 each.

“As a malaria researcher, I used to dream of the day we would have a safe and effective vaccine against malaria. Now we have two,” he said.

The WHO regional director for Africa, Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, stressed the significance of the new vaccine, saying that it “holds real potential to close the huge demand-and-supply gap.

“Delivered to scale and rolled out widely, the two vaccines can help bolster malaria prevention and control efforts and save hundreds of thousands of young lives in Africa from this deadly disease.”

The R21 vaccine still needs to be taken through further steps before it can be purchased internationally for a wider distribution.

The first malaria vaccine recommended for use to prevent malaria in children in areas of moderate to high malaria transmission is the RTS,S/AS01 (RTS,S) that WHO recommended in October 2021, on the advice of two WHO global advisory bodies, one for immunisation and the other for malaria.

The WHO recommendation was informed by results from a Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme ( MVIP) coordinated by WHO that had reached nearly 1.7 million children with at least one dose of vaccine starting in 2019 with more than 4.5 million doses of the vaccine administered through the countries’ routine immunization programmes.

The WHO noted that community demand for the vaccine is high and the vaccine is well accepted in African communities even when several visits to clinics are required to receive the 4-dose schedule.

The makers of the R21 say the vaccine could be made available as early as mid-2024 while the first doses of the RTS,S vaccine are expected to arrive in countries during the last quarter of 2023, with countries starting to roll them out by early 2024.

Uganda listed

Uganda has been listed among 12 countries in Africa that will be allocated a total of 18 million doses of RTS,S/AS01 for the 2023–2025 period.

The RTS,S vaccine was the result of several decades of research and development, supported through public-private partnerships and significant contributions by African scientists and communities. An innovative financing agreement between Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and MedAccess, vaccine doses became available to initiate the Gavi-supported malaria vaccine roll-out.

“The high demand for the vaccine and the strong reach of childhood immunisation will increase equity in access to malaria prevention and save many young lives. We will work tirelessly to increase supply until all children at risk have access,” said Dr Kate O’Brien, WHO Director of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals at the time.

While announcing news of the latest vaccine, Oxford University, said the Serum Institute of India has the capacity to produce 100 million doses a year and can boost this to 200 million doses annually over the next two years.

Reacting to the announcement, the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership noted that the new vaccine will protect children from the most common and deadly form of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum.

Despite the good news of a second vaccine, the RBM Partnership is warning that the vaccines are “not silver bullets designed to solve all the challenges of malaria.”

The partnership’s chief executive, Dr Michael Charles, said countries face different challenges “and will need to determine how R21 and RTS,S can complement their existing malaria control strategies.

“This new vaccine will be highly effective to fight malaria, but must be used in tandem with other tools such as insecticide-treated nets, indoor residual spraying and preventive medicines to have the greatest impact.”

He said while the new vaccine was a step in the right direction, there are also still major hurdles to overcome. He mentioned significant funding shortfalls, growing threats of insecticide and drug resistance, and climate change.

“Further investment must be urgently mobilised to scale-up, manufacture and roll-out malaria vaccines to ensure they are readily accessible to countries that decide to use them,” he said.

High demand

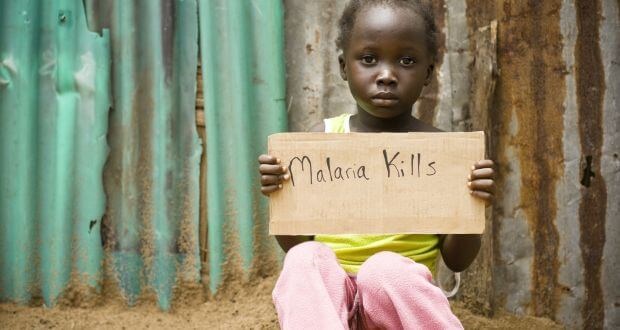

Malaria remains one of Africa’s deadliest diseases, killing nearly half a million children each year under the age of 5, and accounting for approximately 95% of global malaria cases and 96% of deaths in 2021.

Nearly every minute, a child under 5 years old dies of malaria, according to UNICEF. Although malaria has been treatable and deaths have been preventable for a long time, the roll-out of these vaccine is expected to give children, an even better chance at surviving.

However, current estimates suggest that the initial supply of the vaccines is insufficient to meet the needs of over 25 million children born each year in regions with moderate to high malaria transmission.

Demand forecast scenarios suggest that this may translate into a long-term need of more than 100 million doses of malaria vaccine per year (assuming a 4-dose schedule although some countries may decide on a 5-dose strategy). Annual global demand for malaria vaccines is estimated at 40–60 million doses by 2026 alone, growing to 80–100 million doses each year by 2030.

Given the limited supply in the first years of the roll-out of this new vaccine, in 2022 WHO convened expert advisors, primarily from Africa – where the burden of malaria is greatest – to support the development of a Framework for allocation of limited malaria vaccine supply, to guide where initial limited doses would be allocated. The Framework is based on ethical principles on a foundation of solidarity; and it proposes that vaccine allocation begin in areas of greatest need.

The Framework implementation group that applied the framework principles included representatives of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), UNICEF, WHO and the Gavi Secretariat, as well as representatives of civil society and independent advisors.

The group’s recommendations were reviewed and endorsed by the Senior Leadership Endorsement Group of Gavi, WHO and UNICEF.

Affected countries

According to current WHO guidance, moderate to high malaria transmission settings are defined as those with an annual incidence greater than around 250 cases per 1000 population or a prevalence of P. falciparum infection in children aged 2–10 years of approximately 10% or more.

In 2021, while announcing its recommendation of the RTS,S vaccine, the WHO said most of the affected countries were eligible to receive support from Gavi to facilitate vaccine introductions, including the new malaria vaccine.

It said malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme countries Ghana, Kenya and Malawi would receive doses to continue vaccinations in pilot areas.

Since 2019, Ghana, Kenya and Malawi have been delivering the malaria vaccine through the Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme (MVIP), coordinated by WHO and funded by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and Unitaid.

Uganda is among new countries where introductory allocations were made. Other countries in this category are Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Niger, and Sierra Leone.

According to a new WHO births estimate for 2023 by need in sub-Saharan African countries with moderate to high malaria transmission, Uganda has an annual target population of 1.6 million eligible people for the vaccine.

Nigeria has the highest estimated need population of 7.2 million, followed by the DR Congo 3.6, and Mozambique 1 million. Countries with the least estimated need for the vaccine are Equatorial Guinea 25,000, Ethiopia 26,000, Gabon 58,000 and Mauritania 73,000.

In addition to Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, the initial 18 million dose allocation will enable nine more countries, including Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Niger, Sierra Leone and Uganda, to introduce the initial RTS,S vaccine into their routine immunisation programmes for the first time in early 2024.

However, supply of the vaccine is expected to be insufficient to meet the need in the initial years. A recent Global Malaria Vaccine Market Study, commissioned by WHO, found that vaccine supply might be insufficient through the medium term, with a constrained supply potentially during the first 4-6 years following expected first introductions.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price