Access to European markets increasingly depends on surrendering precise farm data under EUDR rules

Kampala, Uganda | RONALD MUSOKE | In the lush highlands of eastern and western Uganda, coffee farmers have long relied on fertile soils, predictable rains, and generations of agricultural knowledge to sustain their livelihoods. Today, however, a new factor has entered the landscape: data.

As the European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) reshapes the global coffee market, Uganda’s coffee story is no longer just about beans and soil. It is increasingly about polygons, GPS coordinates, and control over information.

For smallholder farmers like Ronald Buule from Wakiso District — whose family has grown coffee for generations — the question is no longer only how to farm, but who owns the data generated by that farming.

Adopted by the European Parliament in December 2022 and enforced from June 2023, the EUDR requires that commodities entering the EU market; including coffee, cocoa, soy, palm oil, cattle, rubber, and wood, must be demonstrably free from deforestation, as of December 31, 2020. Failure to comply can result in confiscation of consignments and heavy fines for both importers and exporters, as stipulated under Regulation (EU) 2023/1115. For Uganda, where more than two million people grow coffee — most of them smallholders — the regulation has transformed routine agricultural activity into a complex exercise in digital compliance.

From soil to satellites

Under the EUDR, every coffee-producing plot must be mapped. Farms larger than four hectares require detailed polygons with at least six decimal places of latitude and longitude, precisely defining farm boundaries. Smaller plots require at least one geolocation point. Exporters must compile this information into Due Diligence Statements (DDS), submitted through the EU’s digital TRACES system. Each DDS links exported coffee—down to individual 60kg bags—to its farm of origin, certifying that production did not involve deforestation.

Dr. Gerald Kyalo (PhD), the Commissioner in charge of Coffee Development at the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF), illustrated the process at a stakeholder meeting in Kampala in July 2024.

“If a coffee farmer in Mbale (eastern Uganda) has contributed five bags in a container, when that coffee reaches Europe, there will be a list indicating that contribution, complete with GPS coordinates,” Kyalo said. “EU Authorities can then see the farm back in Mbale and verify, through historical satellite imagery, whether forest cover was cleared after 2020.” If deforestation is detected, the consequences are severe. “Whoever exported that coffee will be fined. The consignment may also be destroyed at the importer’s cost,” Kyalo warned.

The EU’s deforestation argument

The EU argues that agricultural expansion is a major driver of global deforestation. By restricting market access for commodities linked to forest loss, the bloc aims to reduce its contribution to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions as it works toward net-zero targets by 2050.

Although the regulation officially came into force in June 2023, implementation has been repeatedly delayed. Initially, large scale operators were given 18 months to comply, with smaller enterprises allowed 24 months. Enforcement was expected in December 2024, but was then postponed.

On Oct. 2, 2024, the European Commission proposed a further one-year delay, moving enforcement to Dec. 30, 2025. Last year, European Environmental Commissioner, Jessika Roswall, cited challenges with the digital infrastructure needed to process due diligence statements. She proposed another extension of one more year to fix the IT glitch.

“The implementation of the EUDR requires an information system capable of handling all transactions initiated by economic operators inside and outside the EU,” Roswall wrote in a letter to the European Parliament’s environment committee. New projections, Roswall, stated showed a much heavier system load than initially anticipated, driven by small consignments, customs cross-checks, and downstream operator obligations.

“This IT system must be able to handle all the transactions for products covered by the EUDR and initiated by economic operators in the scope of the EUDR, both upstream and downstream, inside and outside the EU,” she said, noting that over the previous year, the Commisison had tried deploying the IT system in close contact with stakeholders.

“In this context, new projections on the number of expected operations and interactions between economic operators and the IT system has led to a substantial upward reassessment of the projected load on the IT system,” Roswall added.

Data security and control concerns

However, while the IT system is designed to ensure traceability and environmental compliance, it has also raised concerns about data governance and sovereignty. Several experts that spoke to The Independent argue that the EUDR is not only about forests—but also about who ultimately controls agricultural data.

At an East African Community (EAC) and Southern African Development Community (SADC) high-level policy dialogue held in Kampala in mid-December 2025, Gideon Gatpan, the Chairperson of the East African Legislative Assembly Committee on Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Tourism, raised the concerns.

“When you link GPS coordinates to satellites, this becomes very complicated,” Gatpan said. “There are (ongoing) trade wars. We don’t want to expose our region or continent to future blackmail… Who is controlling the data?”

Gatpan’s rhetorical question is intriguing. The Independent put the question to the European Union Delegation in Uganda because Uganda’s Data Protection and Privacy Act of 2019 mandates local processing and storage of citizens’ data. Asked where the EU’s interest in Ugandan coffee farmer data begins and ends, the EU Delegation in Uganda declined to comment directly.

Michelle Walsh, the Head of Green Transition and Private Sector, told The Independent in a Jan.27 email that EUDR activities in Uganda are coordinated through a taskforce co-chaired by MAAIF and the private sector, with updates provided exclusively by the ministry.

“The EU Delegation is regrettably not in a position to provide information on EUDR data collection efforts at country level, as such updates are exclusively provided by MAAIF,” she said. MAAIF is the acronym for Uganda’s Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries.

How Uganda’s system works

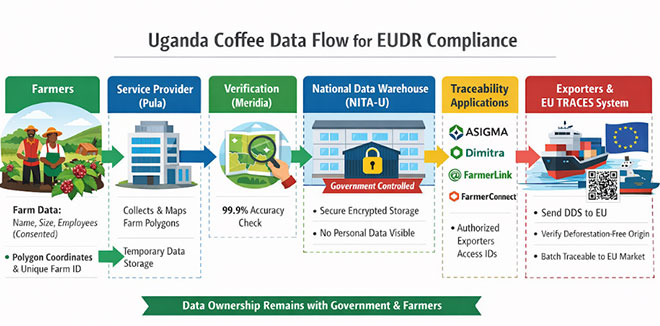

Earlier, The Independent had reached out to Rauben Keimusya, the Assistant Commissioner for Coffee Production at the agriculture ministry to explain how the system works. Keimusya outlined that Uganda’s EUDR compliance framework rests on three pillars: data collection, secure storage, and traceability.

“Farm polygons are collected with farmer consent,” Keimusya told The Independent. He said the data collected from farmers is strictly controlled and “is not open source,” emphasizing that it cannot be accessed freely by anyone in Brussels or elsewhere in the world.

Keimusya said the collected information is locally stored in the National Data Warehouse, hosted at National Information Technology Authority (NITA-U), which acts as the “national data custodian.” “Access is highly regulated; users must be part of approved traceability applications, scrutinized by a committee made up of government representatives, IT experts, and private-sector stakeholders,” he said. “For you to access the data… you must be an approved traceability application.”

“Coffee exporters must first be registered and mapped, ensuring their legitimacy before accessing any data. The applications connect securely to the warehouse via APIs, which allow buyers to retrieve information using a unique farm ID.”

He added: “Even if you are sending someone to sell your coffee at the hulling centre, you send them with your unique ID. They don’t have to know you. This system preserves the confidentiality of farmer information while enabling transactional transparency,” he said. “Data is aggregated and encrypted at every stage, so that even as coffee moves through traders, processors, and exporters, the farm itself cannot be traced directly by unauthorized parties.”

At the point of export, a QR (Quick Response) code aggregates multiple batches, allowing the origin to be verified if necessary: “You can get the farmer where it was grown… using an application which was approved.”

Meanwhile, the collected data also serves regulatory purposes. Keimusya explains that it is used to generate “a due diligence statement” required by the EU, ensuring compliance with international standards while protecting individual privacy. Throughout, monitoring ensures that all actions adhere to the National Data Protection Act of 2019, and no information is shared for purposes beyond selling coffee.

It is this controlled system, Kemusya says, that balances traceability, transparency, and farmer privacy, making Uganda’s coffee supply chain both secure and compliant with global due diligence requirements. “The system verifies deforestation compliance without revealing identities,” he said. “Once a batch is exported, the associated polygons are retired, preventing reuse and fraud.”

Farmer anxieties persist

Yet, despite these safeguards, many Ugandan coffee farmers remain uneasy. Taddeo Senyonyi, a two-acre coffee grower in Kakumiro District, says the process feels opaque. “They took my details—name, farm size, number of employees—but I never received proof of registration,” he said. “You can’t be sure that the data won’t be abused. But without registration, your coffee cannot reach the EU.”

A coffee sector source, speaking anonymously, questioned the broader logic of the approach. “Of all the climate change challenges Uganda faces, is geomapping small farms really the solution?” the source asked. “And if you can trace a farm, how hard is it to identify the owner?”

Concerns also surround the role of private firms in the ongoing data collection process. The data collection and mapping in Uganda has been conducted by Pula, a Kenya-headquartered agro-insurance company, under a multi-consortium arrangement involving farmer registration, exporter registration, and trader onboarding.

The mapping exercise was initially funded by the Agriculture Business Initiative (aBi), a Danish Government-affiliated finance vehicle, which supported registration of 900,000 farms. The Ugandan government later funded a second phase covering 780,000 additional farms. Data verification has been conducted by Dutch firm Meridia, which has apparently reported 99.9% accuracy of the data so far collected.

Maintaining the National Data Warehouse is estimated to cost about US$910,000 annually—roughly US$30–34 per container of coffee exported. According to Brenda Akankunda, the National Coordinator of the International Trade Centre in Uganda, EU buyers have agreed to absorb these costs to prevent them from being passed on to farmers. “So, who ultimately owns this data.? Is it the government, the funders, or the service providers?” the source asked. “And who gets to own it when the project ends?”

Power, sovereignty, and trust

The debate over data ownership remains unresolved. Jane Nalunga, the Executive Director of the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI), a Kampala-based trade policy thinktank, warns of structural power imbalances.

“Data is the new oil,” Nalunga said during the two-day high-level policy dialogue in Kampala. “Without strong state-led registries, private firms increasingly collect, store, and monetize sensitive information, creating power asymmetries.”

Ashlee Tuttleman of VOCAL Network, a global alliance of civil society organisations that are interested and committed to long-term advocacy in the coffee sector, noted during the policy dialogue that control of technology translates into control of markets. “Data leads to knowledge, and knowledge is power,” she said. “Farmers must ensure the information collected benefits them.”

Ronald Buule, the Executive Director of the Central Coffee Farmers Association (CECOFA) emphasizes farmer education. “When something new is introduced, farmers fear taxes and politics. We must show them (the farmers) the value step by step,” he said.

A digital shadow over every bag

As enforcement of the EUDR is delayed again, until December 2026, Uganda’s coffee continues to flow to global markets, but every bag now carries a digital shadow, linking it to polygons, databases, and due diligence statements.

For farmers, this represents both opportunity and vulnerability. Compliance ensures market access, but data misuse could undermine trust and livelihoods. For Uganda, the challenge is balancing environmental responsibility, global trade demands, and farmer sovereignty. Strong governance, secure systems, and transparency will also determine whether traceability becomes a tool for empowerment, or extraction.

As coffee continues to ripen on Uganda’s misty hillsides, its journey from farm to cup is increasingly defined by bytes as much as beans. How Uganda governs these digital footprints will shape not only the future of its coffee sector, but its role in a global economy where data has become as valuable as the commodities it tracks.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price