Harare, Zimbabwe | AFP |

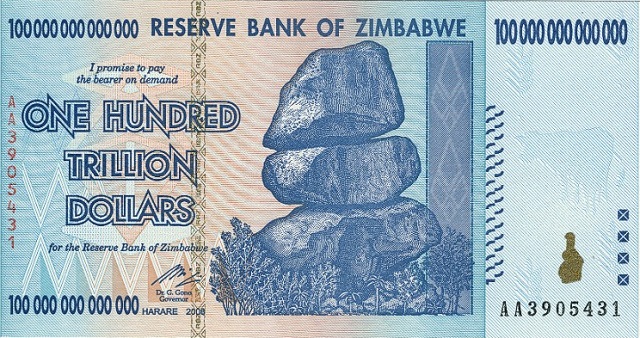

Zimbabweans know the risks of worthless money all too well after hyperinflation between 2007 and 2009 gave them the 100-trillion-dollar banknote that barely bought a loaf of bread.

Now they fear that the government is about to create another devastating crisis by printing its own “bond notes” that will officially be worth the same as the US dollar.

Many Zimbabweans who lost all their savings in the hyperinflation years dread President Robert Mugabe’s government issuing so-called “surrogate money”, set for next month.

“My fear is that we will have a repeat of 2009,” Petros Chirenje, 43, an electrician based in the capital, Harare, told AFP.

“I had 17 trillion Zimbabwean dollars in my bank account and I lost everything when the government switched to foreign currency.

“I worry that the US dollars in my account will be converted to bond notes.”

The country has used the US dollar since 2009 after issuing so many Zimbabwe dollars that hyperinflation peaked at 500 billion percent and the national currency was abandoned.

But a shortage of US banknotes has added to Zimbabwe’s accumulating economic woes.

Banks are scarcely able to dispense cash, the few remaining businesses are grinding to a halt, and the government repeatedly fails to pay soldiers and civil servants on time.

Rush for scarce US dollars

Chirenje buys imported electrical supplies because few goods are made in Zimbabwe — but bond notes are unlikely to have much value to international producers.

“The government says the bond notes will be equivalent to the US dollar, but my question is ‘how?’,” he said.

The new notes, starting with small denominations of $2 and $5, were meant to be introduced this month, and are now due out in November but no confirmed date has yet been announced.

In response, Zimbabweans have been lining up outside banks to try to get hold of the few remaining US dollars. Withdrawals are sometimes limited to just $50 per person a day.

Mavis Chapo, a housewife, said she was withdrawing all her money “before it is eaten up.”

“I would rather take my money out and buy things I did not plan to buy,” 54-year-old Chapo said outside the Central African Building Society bank in the capital, adding she would not give up despite waiting for five hours in the hot summer sun.

“I cried when I lost all the money in my account in 2009 and was later told it was worth only US$5. I am wiser after that experience. I don’t want to cry again.”

The state-run Herald newspaper said last week that “the introduction of bond notes early next month is on course, with massive educational campaigns expected to start on October 31.”

Reserve Bank governor John Mangudya on Thursday sought to allay fears that authorities were using bond notes to covertly re-introduce the Zimbabwe dollar.

“These are just short-term measures,” he told a meeting of local business executives in Harare.

“The long-term measures are to ensure that the economy is investor-friendly.”

He said bond notes would be introduced gradually, and claimed they would help boost exports and production as well as the cash crunch.

Investors flee

Such reassurances are unlikely to persuade investors who have pulled out of Zimbabwe due to the authoritarian regime of 92-year-old Mugabe, laws forcing foreign-owned companies to sell majority stakes to locals, and endemic corruption.

At least 4,600 companies have closed down in the past three years, according to central bank data cited by Bloomberg News.

“The bond notes are not a solution to the liquidity crisis,” Obert Gutu, spokesman for the main opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) party, told AFP.

“This is a dead end and the talk of bond notes is causing anxiety and panic as shown by the numbers of people going to make withdrawals.”

The bond notes plan, which was announced in May, hit a further snag last week with reports that the German company that was to print the new currency had pulled out of the deal.

“No one can trust the government,” Tony Hawkins, professor at the University of Zimbabwe’s school of economics, said.

“It seems the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing and this is not good for the economy.”

A wave of protests this year has shaken Mugabe’s 36-year rule, with “No to bond notes” among the slogans at anti-government demonstrations that have been regularly crushed by police.

The government says the new notes will be backed by a $200-million support facility provided by the Cairo-based Afreximbank (Africa Export-Import Bank).

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price