By Maya Prabhu

Hot deals lure mobile money subscribers into cash-less class

Mobile money first became available in Uganda a little over a year ago, and represents potential solution to the poor access to financial services that is a problem in many developing countries. In neighbouring Kenya, Safaricom has already proven that mobile money can take off as a cheap and accessible money transfer system.

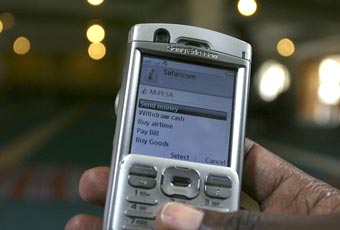

With over 9.5 million registered users as of April 2010, Safaricom’s mobile money platform, M-PESA, is a huge success. Its achievements are so far unparalleled on the entire continent. However, with three leading mobile operators now offering mobile money to the Ugandan market, market insiders hope that the Ugandan economy, too, will be transformed through mobile finance.

Mobile money transfer was initially attractive as a safe, efficient and cheap means for poorer urban migrants to send remittances to their families in rural areas. Cutting out long, expensive journeys or the risk and cost of entrusting valuable and hard-earned money to bus and lorry drivers, mobile person-to-person money transfer represents a tremendous benefit to the poorer classes in countries like Uganda. But mobile money has the potential to be more broadly relevant, and has begun its evolution into a more inclusive, more comprehensive financial system.

This is facilitated by the fact that it is relatively simple to open a mobile money account or ‘e-wallet’. The long list of conditions for opening bank accounts exclude the largest proportion of Ugandans, but the ‘Know Your Customer’ requirements for mobile banking are much laxer. A school or company ID will suffice in the place of a passport, driving license or voter registration card, and if a prospective customer doesn’t own any of those, a brief reference letter from his LC will do.

Additionally, mobile banking is less intimidating than entering the formal economy your mobile banking agent, quite possibly the same vendor from whom you’ve been buying airtime for years, replaces the unfamiliar and often more remote bank tellers and ATMs.

Although users are unable to earn interest on mobile money, ‘e-wallets’ already represent a form of savings account for some. Mobile money is not kept on user’s simcards but on a central server, which protects it from loss and theft. For many, mobile money offers a safer savings option than cash.

The evolution of the product itself is making it attractive to a more diverse customer base. Mobile financial services may have begun as a product for the unbanked poor, but it is not only the poor who can benefit from it now. In Kenya, for example, airline tickets can be purchased through M-PESA, and a recent partnership between Safaricom and Equity bank, called M-Kesho, allows customers to transfer funds in and out of their bank accounts using their mobile phones. In Uganda, too, the evolution of mobile banking is yielding facilities targeted at customers further up the social scale.

New applications like school fee and bill payment functions could actually improve domestic productivity by saving working people the time normally spent in queues, and a 2009 study by the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) says that, at low transaction values, using e-wallets and mobile money transfers is on average 38% cheaper than going through formal financial channels.

Phil Levin, Director of Mobile Banking with MAP international, an American company partnered with UTL on mobile financial service platform, M-Sente, underscores that it is important to recognise that mobile banking is only in its infancy, and is capable of having a tremendous impact in future years. “In 2010 mobile money is about money transfer. It could be that in 2015 it’s about savings. What this means is that it’s taking cash out of the day-to-day economy and facilitating the evolution of the Ugandan financial system from an informal, to a formal economy.

The promise of mobile money paints an exciting picture of the future. But is Uganda actually on the way to fulfilling service providers’ mobile ambitions?

MTN, who launched Uganda’s first mobile financial service platform in March 2009, recently announced that MTN MobileMoney has hit the 1 million subscriber mark. At the end of June, they anticipate reaching 1.1 million users. Zain’s mobile commerce platform, Zap, has gained 103,000 registered users since their launch on June 29, 2009. While representatives of UTL’s three-month old M-SENTE mobile banking service were reluctant to release expansion figures prior to an upcoming promotion, CTO Menghistab Tesfai said M-SENTE is approaching 50,000 registered users.

With well over a million Ugandans subscribed to use mobile banking, a much larger number will have been at the passive end of mobile money transactions, since recipients of mobile person-to-person transfers do not need to be registered users.

But, a little over a year after the birth of Uganda’s mobile money market, the cumulative number of mobile banking users in the country is dwarfed by the two million M-PESA subscribers a year after its launch in Kenya, March 2007. The total number of registered mobile finance users in Uganda today still falls far short of 1.5 million.

It is too early to say whether Uganda’s mobile finance scene is likely to lag behind Kenya’s in the long term. For now, Safaricom’s business model provides a successful example, elements of which are worth emulating, say representatives of Uganda’s mobile money providers. Safaricom’s marketing strategy and extensive distribution network seems to represent the envy of mobile money operators. Tesfai at UTL says distribution and ‘experiential, foot-soldier marketing ‘ cannot be underestimated in explaining Safaricom’s success. Direct, one-on-one marketing allows for not only raised awareness but, crucially, improved understanding of what might strike prospective customers as not only a novel, but a profoundly abstract way to deal with money.

Not only UTL recognises the value of Safaricom’s marketing style. MTN have worked with marketing group Top Image, previously partnered with Safaricom. Zain’s Brandon Ssemanda, Marketing Manager with Zain Zap said that his company too, has taken a leaf out of Safaricom’s book: ‘Zap has had to change [its marketing] to take a more direct approach… We now have a one-one-one engagement with customers below the line.’

But Uganda will not just be following in its eastern neighbour’s footsteps. Where M-PESA has a virtual monopoly of the Kenyan mobile money market, Uganda’s mobile financial service providers face hotter competition. Though MTN MobileMoney, launched first, is currently leading the market, UTL M-Sente and Zain Zap have no intention of being eclipsed by their competitor’s early gains. The competitive climate may, indeed, work against the companies who will be battling it out for top spot on Uganda’s mobile money market, since Safaricom’s market dominance in Kenya facilitated the spread of the distribution network that Tesfai pointed to as the cornerstone of their success. But Phil Levin points to another potential byproduct of competition: innovation.

Challenged for their place in the market, especially as the market progresses towards saturation in future years, these companies are more likely to make improvements and adjustments to their mobile finance platforms, which could spur on the evolution of mobile money as a financial system.

By the end of June, each of Uganda’s three mobile banking providers will add several new applications to their platforms. These new features seem to be coaxing mobile banking up the social scale. MTN will allow customers to pay their DSTV bills, and, together with their partner-bank, StanBic, is working on a ‘send money to bank’ facility, which, much like M-Kesho, will make mobile financial services attractive to the already formally banked classes. A ‘bulk payment’ application will allow for the disbursal of, for example, salaries to many workers at once.

Zain, too, plan to roll out a link between mobile financial services and formal bank accounts before the end of June, and like MTN, hope to release a larger-scale ‘merchant payment’ system which will allow customers to use mobile money at supermarkets, not just one-man-cornershops.

Zain’s school fee payment system focuses on schools in and around Kampala, the wealthiest area of the country, and UTL so far only allows for fee payment at Makerere University. Does evolution mean mobile money turning its back on the poor? No, say representatives of all three mobile companies. Tesfai at UTL says the wealthier classes are just, ‘the low-hanging fruit’ an easy source of income, but a population that will never form mobile money’s most important customer base.

Beyond the development of new technologies and applications, innovation means forming new partnerships. MTN’s Junior Kwebiiha says “the rural area is nothing new to us, we have been there, and we know what they are looking for” as he launches into an explanation of how bulk payments and peer-to-peer transfer can make microfinance institutions and their clients relate more easily. The often weekly, small repayments which demand long cycle rides or transport as expensive as the loan repayment itself, could become a thing of the past.

But Phil Levin and Menghistab Tesfai remind us that, although UTL will also launch an M-Kesho type system in order to keep up with the pack on application developments, for now the main and most important ‘killer application’ is still money transfer. Advanced usage of mobile banking ” beyond the more basic functionalities of the ‘e-wallet’ ” is a long way off. ‘Innovation in products is there” if we don’t control ourselves, we’ll spend all our time on this: it’s exciting and interesting. But that can take your focus away from what really needs to be done” says Tesfai.

What needs to be done? Distribution and agent networks need expansion, Uganda needs time to get comfortable with an ‘e-wallet’ in the place of cash. It is too early to tell whether mobile money will boom in Uganda, and difficult to measure the impact of competition at a time when even the ‘low-hanging fruit’ have not yet been plucked. Growth figures look steady, the product itself is advancing, and the longer-term economic impact of mobile money might indeed be huge, but for the immediate future, Uganda’s mobile money market should be regarded with measured optimism.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price