By Jocelyn Edwards

Experts could demand renegotiation of Uganda’s PSAs

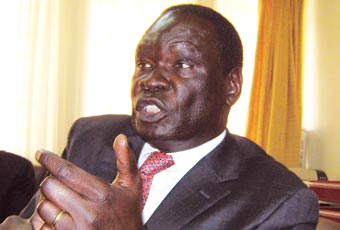

In response to the June 29 tabling of the Petroleum Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) by Energy Minister Hilary Onek, Rubanda West MP Banyenzaki says parliamentarians will seek expert analysis in order to determine whether or not they are fair to Uganda.

Banyenzaki says that renegotiation is a possibility if the PSAs signed with foreign oil companies turn out to be unfavourable for Uganda.

“We shall weigh them and see if they were a good deal or a bad deal. If there are clear loopholes then we shall demand [renegotiation],” he says.

Government had been under pressure from civil society, parliamentarians and media for the release of the documents for several months now, with some accusing it of concealing agreements disadvantageous to the country.

The oil companies have maintained that they have nothing to fear from the release of the PSAs. Operators have at various times declared that they would not object to the government making the documents public, with Tullow Uganda going so far in recent weeks as to suggest that they actually should be released.

Companies have long claimed that once the PSAs were revealed, Ugandans would see that they had obtained agreements that were more than fair. Last year, Tullow’s CEO, Aidan Heavey told The New Vision newspaper that, “Uganda secured one of the best deals in the world for its oil exploration.”

When he finally appeared before parliament to table the deals, Onek told MPs that under the deals the government’s share of oil revenues would rise as production levels went up. Uganda’s PSAs compared “very well” with those of other oil and gas producing countries, despite the fact that they were negotiated when the country did not have proven petroleum reserves, he said. Onek stated that according to the agreements the total take for the government is on average 70 percent adding that in later contracts the government’s share rises to as much as 80 percent when production levels are high.

Yet the very argument Onek made in defence of the PSAs has been one of the main sources of criticism against them. A major flaw in the documents is that government take is calculated according to the number of barrels produced. This assumes that volume of production is the only factor in determining field productivity.

A confidential IMF analysis of the documents revealed in December 2008 by The Independent found that because of this Uganda stands to loose out on a huge share of profits from rising oil prices. The structure of the contracts leaves that economic rent for the oil companies. In fact, “the government take, undiscounted, decreases as the oil price increases under the existing fiscal regime.” In other words when the oil companies are making the most money, the government’s share of profits actually goes down.

The outline that Minister Onek gave of the PSAs he tabled offered nothing to counter concerns about Uganda loosing out on profits when oil prices are high, suggesting that these criticisms are legitimate. So if parliamentarians find the PSAs are indeed wanting in this respect what are the prospects for renegotiation?

Conventional wisdom has said that any attempt at renegotiation would be abject failure. Governments have kept quiet for fear that even the mention of re-opening contracts would spook investors and drive their dollars elsewhere. But MP Banyenzaki says he is not concerned about this. “Business people will always move where there is business. There are so many people who are interested in deals [with Uganda].” The wrangles between Italian oil giant Eni and Tullow and its proposed partners, CNOOC and Total, suggest he may be right.

And the idea that African governments could and should revisit weak contracts has started to look less like a radical idea in recent years. The idea gained traction most recently with a joint study by the OECD and the African Development Bank presented at the bank’s Annual General Meeting in May. “Multinational enterprises may threaten to leave but they are unlikely to actually abandon the exploitation of mines [or oil assets] because of a reasonable rise in taxes or royalties,” said the study.Interest in the continent’s natural resources by China, Brazil and other emerging economies offers African states further opportunities to maximise profits from natural resources through competitive bidding, it pointed out.

Some countries on the continent have already started demanding greater profits for their mineral wealth. Two years ago, the Democratic Republic of Congo undertook a review of mining contracts concluded during the war in that country. But just because countries have re-opened their contracts does not mean that they have been any more successful in obtaining fair terms than when the documents were first written.

The mining sector review in the Congo largely failed to obtain its objectives, with the government accepting one-time upfront payments and loosing out on any real long term benefits. Experts have put the failure down to, among other things, a lack of support from the international community and a lack of transparency in the review process.

The tabling of Uganda’s PSAs is a real victory for transparency in the nascent industry; it shows that the executive is responsive to pressure on petroleum matters. The documents’ release was achieved through sustained pressure from MPs, media and civil society. If parliamentarians find the contracts unfair to Uganda, they will have to push just as hard to galvanise support, both at home and abroad, for renegotiation.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price