Agencies

In this article from Ratio Magazine, Andrea Bohnstedt speaks to Duncan Clarke, the Chairman and CEO of Global Pacific and Partners (GP&P), about Uganda’s emerging hydrocarbon sector, the creation of local refining capacity, and prospects for the sector in East Africa.

Developments in Uganda’s petroleum sector have accelerated recently, after several finds have confirmed the commercial viability of the oil field. Do you think Ugandan authorities are prepared for the transition to an oil-producing economy, or will at least be able to catch up quickly in setting up the necessary regulatory, institutional and policy environment?

Uganda’s oil game is on a roll. Large and growing reserves, with open acreage, and new potential have shifted Uganda from a landlocked frontier to a new producer and potential crude/product exporter. Naturally, a new oil regime is needed to manage this transition. And government has thought on this matter and its options, in cases taking advice from outside, for example from the Norwegians. The key question is less the task of installing a new framework but the focus and quality of that structure. Ideally, the new state oil company should have a commercial orientation, and be able to be an equity partner in ventures on a self-funded basis. Any petroleum fund to manage net forex surpluses should be structured so that inflationary effects and macro distortions are minimised, while investments are focused on infrastructure and not consumption, especially by the state. Temptation to follow the charms of resource nationalism should be resisted, and the tax regime kept highly competitive since new ventures will still be needed, acreage must be leased, bid rounds run, and investor companies expect continuity in tax treatment with no lurch to the boundaries of creeping nationalisation – a long term kiss of death for a country such as Uganda.

President Museveni had been emphatic that Uganda would not export any crude, but refine locally to ensure that value addition remains in the country. The Uganda government estimates that the East African demand alone is sufficient. Do you think this is the right way forward?

Much will depend on reserves, the total volumes of which are not yet fully known, and long term oil production profiles, as well as crude qualities. To take a dogmatic view that no crude will be exported is unwise, short term in outlook, and cannot be justified by mere politics or ideology, as it needs an economic evaluation to support such claims. Why shoot oneself in the foot, if it is cheaper and more beneficial not to? The reality is that there are probably several ways to skin the cat: A small domestic refinery for local product demand, and so on, might work and find some justification, but scale mitigates against efficiency and costs. A large refinery to absorb all crude means heavy investment, and potential delay in crude exports, while no one really knows how the profile might or might not be influenced by future discoveries and their size. Then there is the need to solicit a refinery investor of substance. This takes time and costs for investment can be substantial, while the investor must take a view on sovereign risk as well. I think crude export initially is the way to go, to realise early benefits, allow time for more exploration, permit a small plant to maybe become a local facility for the domestic/regional market, and avoid the possible risk of a refinery white elephant which would need to compete with imported products.

How do you perceive investor interest in the resulting downstream opportunities? Does this sector attract serious global players? Are there any comparable countries in Africa where this industry has been built from scratch? What are the experiences from those countries that Uganda needs to bear in mind“ both positively and negatively?

My answer comes with the caveat that downstream risk assessment is not our forte. But the refinery risk would be the greatest, much less than a crude export pipeline via Kenya, and equally less than in storage, retail and distribution. Many African refineries have been closed or remain uneconomic, while new plants have long lead times, have incurred delays, e.g. in Angola, and face stiff global competition. All of this would be magnified inside a landlocked state even if the government is supportive, and the environment benign. Elsewhere, Sudan has built refinery capacity but remember it has long been a producer, and its volumes well exceed Uganda’s likely early three to five year production flows.

On a continental level, how much of a player do you expect East Africa to be? On a regional scale, Uganda currently appears to be most promising. What is the feedback in the industry?

With the exception of Sudan, East Africa is a small gas player at this time, and oil will rebalance its hydrocarbon bounty and impact on the markets, both local and regional, as well as elsewhere. In time, with Madagascar, and perhaps also Tanzania and Kenya (if there are decent oil discoveries), we might see a stronger profile. Several frontier states hold promise to be oil producers: Ethiopia, Eritrea, Seychelles, and Mozambique. All are at an early stage of exploration. So far, Uganda has led the pack, and all countries are soliciting exploration players. The industry is generally positive to the wider area, and acreage pick up has been substantial between 2001 and 2009.

What is the future for East African oil and gas?

I think there is a promising exploration and production future for the wider region, from Somalia to Mozambique, onshore and in new basins that have been little explored, even into the Great Lakes. But governments must run a world-class race: with regular bid rounds, opening up opportunities, improving the terms if necessary, setting out firm and sustained investment and policy guidelines, operating above board, creating competitive and even landscapes (including for state players, their own amongst others), refraining from politicisation of the oil game, and nurturing sound business relationships with the companies.

****

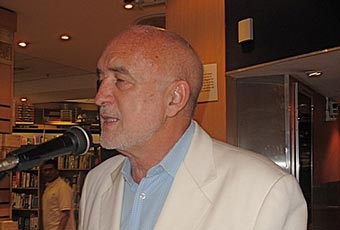

Dr Duncan Clarke is the Chairman and CEO of Global Pacific & Partners, a leading advisory firm on the hydrocarbon sector.He is the author of several books on the gobal exploration industry, including Crude Continent: The Struggle for Africa’s Oil Prize (Profile Books, London, 2008)./

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price