Two years’ delay before there is a referendum will give opportunity for feelings to be inflamed and for passions to be played upon, with every risk that they will lead to a situation which cannot be settled peacefully.

A referendum when carried out by an independent State cannot be supervised by outside impartial authorities. The changes in the Constitution and territorial changes in the new State have to be passed by a two-thirds majority. Everything depends on the two-thirds majority.

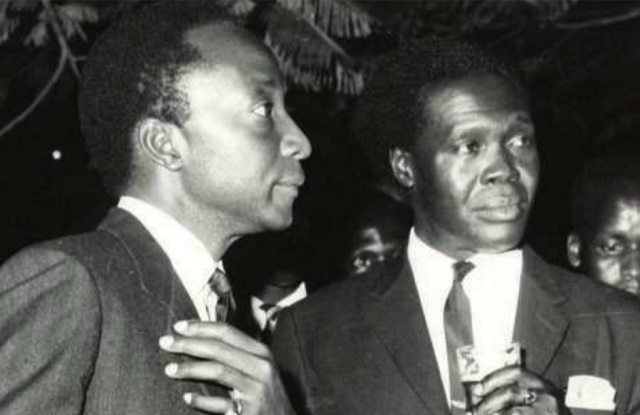

At the moment I understand that Mr. Obote is leading a Coalition Government and his principal supporters are the Buganda Party.

The Buganda Party have gone on record as saying that they are irreconcilably opposed ever to giving the control of any of the disputed counties to another kingdom. That is what leads one to look on the situation with some alarm. We think that Her Majesty’s Government have taken the wrong decision and have shirked their responsibilities. There is hope that the peoples of Uganda who, after all, have recognised the value to them of a peaceful combination to make the new state a success, may see that, no matter what they feel now, some compromise by both parties to the dispute is inevitable.

But that sort of attempt requires mutual confidence on both sides, and the confidence of the smaller of the two disputants, Bunyoro, is not likely to be forthcoming when you get threats expressed like those reported in The Times of July 19, when the acting Buganda Premier said: “The Kabaka’s people had been prepared to invade Bunyoro if Britain had ordered any of the Lost Counties to be transferred.” That is not the kind of language calculated to permit a peaceful settlement.

We can only hope that more moderate counsels will prevail; that the future will be assured; and that this country, which has been, as the noble Marquess said, such a good example of a Protectorate under the British Crown, thanks to the devoted efforts of the British Colonial servants, will continue on its path of independence. We hope that the dispute between these two component parts is settled peacefully. I would extend our warmest wishes to the peoples, all of them, of Uganda.

LORD OGMORE

My Lords, I feel that the prospects of Uganda are bright, because, unlike so many countries whose independence we celebrate in this House, it is economically viable. It has a small population for its size—only some 6 million or 7 million in a country the size of Britain—and it has a rich soil, with many natural resources. There is no large settler element there and there is no large racial minority. Such racial minorities as are there are badly needed in the development of the country; and I am sure— indeed, I know—that this fact is understood by the African leaders. Politically, therefore, so far as those problems are concerned—problems which are so acute in other parts of Africa—there is no difficulty in Uganda.

As the noble Marquess said, the acute problem was over the lost counties. Originally, there were six, and now, as the result of the Report of Lord Molson’s Commission, that is cut down to two. There were three courses which we at the Conference thought that the British Government might take. The first was to give the two counties to Bunyoro; the second, to allow Buganda to retain them for all time, as it were; and the third was to do nothing. After some experience of

Her Majesty’s Government, I must admit that I was afraid they would take the third course and do nothing. It seemed to me highly important that they should do something. It was quite beyond reason to expect a young Uganda Government to handle a problem of this kind which was, in any case, sixty years ago the responsibility of Her Majesty’s Government, and on which nothing has been done ever since.

So I was very glad indeed that they took action and did take a decision. It was quite an unexpected one—namely, that the Central Government should administer these two counties for a period of not less than two years, after which the decision should be taken by a referendum organised by the National Assembly of Uganda. I thought that was quite an imaginative proposal. It was a decision which was accepted by the Uganda Government. It was a great step forward.

Mr. Obote, with great courage I may say, accepted the decision, and I think it may well be that it will be found in time to be the right one. The only question in my mind is whether there should be a maximum period as well as a minimum one—in other words, whether the referendum must be held within a certain period of time. But, on the whole, I think it is perhaps just as well not to include it in the Constitution. If a declaration can be obtained from the Uganda Government, so much the better. All these things will be in the hands of the Uganda Government, and I personally have every confidence in Mr. Obote. I think he is a remarkable man and, so far as he is concerned, I am sure he will carry out any obligations to the letter.

VISCOUNT WARD OF WITLEY

My Lords, I have never regarded myself, and certainly no one else has ever regarded me, as an expert on Colonial Affairs, and I ventured to intervene briefly in this debate to-day only because I was one of the three Privy Counsellors, under the leadership of my noble friend Lord Molson, who, at the request of the Prime Minister, visited Uganda last January to inquire into and report upon the long-standing boundary dispute between Buganda and Bunyoro. Anyone who has once been to Uganda will, I believe, always take a close interest in its future development.

For one cannot fail to be captivated by the beauty of the country and by the kindness and charm of its people; nor can one fail to recapture much of the magnetism which compelled the great Victorian explorers to return there again and again, determined, in spite of immense hardship, danger and disease to uncover the wealth of secrets it held.

But, my Lords, even in a maiden speech which I know must not be too controversial, I cannot refrain from expressing my disappointment that it was not found possible to get agreement between Buganda and Bunyoro over the lost counties dispute before the date of independence. As the noble Marquess has said, our Commission recommended

that two of the counties should be returned to Bunyoro and that the other four should remain in Buganda.

We also recommended that Mubende Town should be placed under the administration of the Central Government. Those recommendations were accepted without reservation by Her Majesty’s Government and, I think, by Her Majesty’s Opposition as well.

The Omukama of Bunyoro, although disappointed that we had not recommended the return of all the territory, generously agreed to this compromise in the interests of peace, stability and the unity in Uganda as a whole, and he renounced all claim to the four remaining counties. And if there could have been an equally magnanimous gesture by the Kabaka of Buganda, the problem would have been solved and the dispute settled for all time. But, unfortunately, the Kabaka, doubtless with the Kabaka Yekka breathing down his neck, refused to cede any territory at all.

As we know, my right honourable friend produced an alternative solution Which was agreed by Mr. Obote, but, unfortunately, by neither the Kabaka nor by the Omukama.

It is that these two counties of Buyaga and Bugangazzi should be placed under the administration of the Central Government for a minimum period of two years and then a referendum held at some appropriate time to determine the wishes of the people. I have read carefully the arguments put forward in another place that there should be a maximum period within which the referendum must be held as well as a minimum cooling off period, and I must admit that I have some sympathy for the views expressed; but I very much doubt whether it would really be practical politics.

One reason (and I think my noble friend Lord Molson will agree) why our Commission was so anxious to get this matter settled before the date of independence was precisely because we felt it would be impossible to bind the Uganda Government to settle it after the British had gone. And, of course, the same thing applies here. One cannot bind them to stick to a maximum period.

In any case, I am sure Mr. Obote wants to get the matter settled. Indeed, I believe that both the major political Parties in Uganda want to get the matter settled, although I am not so sure about the Kabaka Yekka, which unfortunately holds the balance of power. But, certainly, Mr. Obote will be in the best position to judge the right moment to hold a referendum, and certainly in a better one, I think, than we are now at a distance of two years away.

Whether or not a referendum will work at all depends largely upon the kind of administration which the Uganda Government establishes in the two counties in the next two years. Certainly, it would not work now. As we said in our Report: “a referendum would inevitably fan the flames of tribal feeling, would invite intimidation, and would create a situation in which no lasting settlement could be expected. At worst it could lead to bloodshed.” I cannot help feeling considerable doubt whether this will not be equally true two years from now. Certainly, Mr. Obote is shouldering a very great responsibility. There will be—and I am sure he realises it—much preparatory work to do in the selection of local chiefs, for example, and insistence upon absolute impartiality in their administration. Supervision must be both independent and strict. Security arrangements must be efficient and unbiased.

In that connection, I wonder if I might ask the noble Marquess, when he replies, whether he can give us any idea of the position with regard to the two companies of King’s African Rifles in Uganda; whether he is satisfied that they are properly equipped and there in adequate numbers to deal with any troubles that may arise; and, if not, whether he will assure us that the Government will give them all the help they can. Much will depend upon the two tribes themselves. Any needling of one another, and, particularly, any acts of lawlessness, will tend to perpetuate an atmosphere in which a referendum is impossible. But we can only look on the bright side and hope that things will change considerably in the next few years.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

I’m impressed, I must say. Rarely do I come across a

blog that’s both educative and amusing, and let me tell you,

you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something not enough people are speaking intelligently

about. I am very happy I stumbled across this in my hunt for something relating to this.