Experts blame ‘weak’ govt, disjointed policies

Kampala, Uganda | THE INDEPENDENT | In a new paper titled ‘The political economy of reviving industrial policy in Uganda,’ Pritish Behuria; a Professor in Politics, Governance and Development at The University of Manchester, attempts to explain why Buy Uganda Build Uganda (BUBU), a domestically oriented industrial policy of the government, has had limited success.

Domestically oriented industrialisation policies, such as BUBU, include protectionist policies (such as banning the import and sale of used clothes), using public procurement to support the consumption of domestically manufactured goods, and securing the domestic market.

But the market-led policies of the 1980s have contributed to empowering anti-industrial policy coalitions within government which, along with the World Bank, continue to resist domestically oriented policies such as BUBU.

Behuria examines in detail the contemporary constraints to industrialisation by analysing Uganda’s failed attempts at banning used clothes and using public procurement to promote domestic consumption of locally produced goods.

Behuria says: “Rwanda implemented similar policies to which President Paul Kagame’s government has remained committed. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s government, on the other hand, has wavered. I was keen to understand why.”

Behuria argues that while research has been on political constraints to industrial policy, placing the blame on a singular villain: government corruption, and framing politics as ‘evil’ there is need to look at policies.

He says failure has come about partly because the Ugandan government has replicated domestically oriented industrial policies implemented elsewhere, without adapting them to local political realities. “This has resulted in significant resistance to industrial policies, which showcase the salience of the legacies of past policies,” he says.

“Experiences of all successful late industrialisers tell us that experimentation with policies, rather than replication, resulted in better outcomes,” he says.

Worryingly, Behuria says, “these ‘heterodox’ policies are being replicated with limited adaptation to specific contexts, paralleling the challenges of one-size-fits-all market-led policies.”

Donor resistance

He says policies to support BUBU are not fully implemented and it continues to face resistance from donors. He blames this on “limited regime strength and restricted policy space.” He adds that BUBU policies “are not sufficiently adapted to political constraints.”

Domestically oriented industrial policies cater to the demands of domestic firms, which primarily produce for the home market. However, export-oriented firms, often the government’s preferred partners, resist such policies if the preferential access to Western markets might be withdrawn.

He contrasts this with the ‘export-first’ industrialisation strand which favours foreign investors through policies such as providing tax benefits to industries in Special Economic Zones or supporting them to relocate factories in order to access Western markets through duty-free bilateral agreements, such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) of the American government.

He mentions how Uganda and other East African countries announced a goal of banning (and raising tariffs on) second-hand clothes to boost domestic apparels production but there has been variation in implementing the ban. South Africa and Zambia did the same.

The strategy included public campaigns to encourage domestic consumption of locally produced goods and public procurement was restricted for domestically produced goods. These campaigns ranged from ‘Made in Rwanda/Ghana/Botswana/Nigeria’ to ‘Buy Uganda/Kenya, Build Uganda/Kenya’ campaigns, to ‘Proudly South African.’

Uganda, Rwanda and Kenya increased import duties on used clothes and then banned their imports. Other African countries have been using public procurement to secure domestic markets. They include South Africa, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, and Ghana.

But Uganda has failed to prioritise important sectors. At the time, the U.S. threatened to withdraw its preferential AGOA market, in what Behuria argues, is a clear sign of how such bilateral trade treaties constrain the ability of a country to enact domestically-oriented and export-first policies.

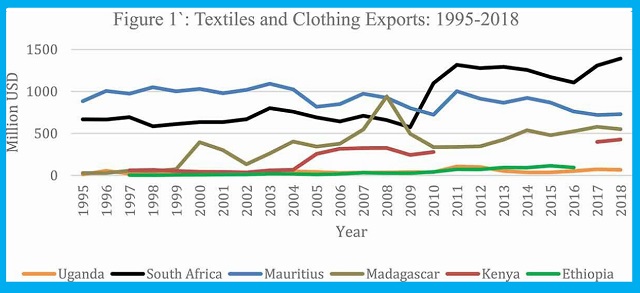

He says AGOA success stories such as South Africa, Madagascar, Mauritius and promising regional neighbours Kenya, Ethiopia have pushed ‘export-first’ strategies using the special economic zones to promote exports.

“In contrast, Uganda’s industrial policies have been less consistent, neither taking advantage of preferential trade agreements nor securing the domestic market,” he says.

He adds that government departments have been split on which industrial policies to pursue and firms have had conflicting interests.

“This has meant Uganda, which was Africa’s largest cotton producer in the 1960s, has been unable to capitalise on its historical advantages,” he adds.

He says although the government is aggressively pushing an industrialisation policy and diversification, has invested heavily in infrastructure, established industrial parks, attempted to promote local content, and attracted some foreign investors for key ‘demonstration effect’ of industrial growth, the domestically-oriented policy has not succeeded.

He says policies remain disjointed, the ministry of Industry retains limited power, and although industrial policy has become important, it is still a low priority.

Behuria’s conclusions are based on interviews conducted with government officials, apparel firms, business associations, journalists, and consultants between March and April 2018 in Uganda and other research.

As a result, firms with conflicting priorities (in terms of end markets for their production) have gained prominence in the absence of a directed and consistent national industrial policy.

To illustrate, he uses two apparel firms; Fine Spinners (export oriented) and Southern Range Nyanza (domestically oriented). He says the government has failed to develop reciprocal relationships with both firms in terms of upgrading their production and export markets, signaling the government’s continued failure to prioritise the sector’s growth.

Southern Nyanza, formerly Nytil, which targets the local and regional market says it has had difficulties strengthening domestic linkages because ‘every segment of production is liberalized, traders tempt farmers to sell raw materials, and the government has failed to support the industry by not even implementing the policies it previously promised, including the National Textiles Policy.

Fine Spinners is a joint venture between UK-based Plexus Group and two Kenyan companies (Bedi Investments and Nakuru Fibres). It initially invested US$40 million to take over the assets of LAP/Tri-Star Apparels. In 2017, it invested in a factory previously operated as Phoenix Logistics.

He says Fine Spinners made quick strides in securing access to external markets, taking advantage of Preferential Trade Areas (PTAs) like AGOA and the European Union’s Everything But Arms (EBA) scheme.

Links to a prominent European buyer – the Cotton Made in Africa Initiative, a German label funded by Michael Otto and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – were already established and within three years, 40% of Fine Spinners production was exported.

Fine Spinners was supplying garments to H&M, the PVH group of companies, and even niche brands like those owned by Kanye West and Michael Jordan.

But Behuria says the firm was conscious of the difficulties in maintaining consistent orders with Western buyers since suppliers were ‘cognizant of human rights challenges.’

“Company representatives mentioned that they lost Calvin Klein contracts when the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act was passed in 2014,” he says.

The Fine Spinners management acknowledged President Yoweri Museveni’s ‘personal support’ but says “not all promises have been kept”.

Smuggling and Chinese imports are recognised threat.

“A tax regime is needed where foreign clothes should cost more than our locally produced clothes and we know this in government but it is difficult to implement,” a government official reportedly told Behuria.

He says the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank have led the charge against domestically-oriented industrial policy.

“They have consistently dissented publicly against domestically-oriented industrial policies. And the comparatively weaker Ministry of Industry, Trade and Cooperatives has struggled to enact industrial policies,” Behuria says.

He says this is a result of how the balance of power within ministries has shifted to budgetary ministries, prioritizing limited wastage. Yet, he says, if experimentation is central to successful industrial policy, wastage would be inevitable.

This case shows how domestic coalitions, with technical support from international finance institutions, can obstruct implementation of policies, including both BUBU and the attempt to raise tariffs on used clothing.

This is partly because, based on the dependence on primary commodity exports for foreign exchange before and after independence, it is feared that reduction of commodity exports to boost domestic manufacturing may result in foreign exchange shortages. In turn, this makes it difficult to pay for imports.

Behuria says most African countries remain constrained by this challenge yet, as many face a loss of exports and a foreign exchange crunch, they may become even more reliant on foreign finance.

Analysis of industrial policy should not focus on constraints only by looking at either the technical (industrial policy instruments) or transitional (how the powerful oppose) costs.

He says there should be intellectual space to think about how politics may shape possibilities rather than just be an impediment.

“The pursuit of pluralist policies in Africa is being hamstrung by the dominance of neo-classical economics at universities and budgetary ministries. This means that there is little space to push against the market-led assumptions associated with the policies of multilateral financial institutions,” he says.

“That’s why there has been little uptake of domestically-oriented industrial policies in Uganda. The Uganda government continues to prioritise supporting export-oriented firms. And the current domestic policy environment doesn’t allow for support for firms that produce for the domestic market,” he adds.

One necessary debate is whether any ‘new’ industrial policy should be market-conforming or market-defying. Market-conforming proponents argue that countries should not experiment with investing in sectors too far from their comparative advantage.

Market-defying optimists argue that the historical record shows that countries like South Korea had some success in picking winners in sectors quite far from their comparative advantage.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price