Army in denial?

Dr Emilio Ovuga, a professor of psychiatry and mental health at Gulu University also told The Independent on July 16 that PTSD is not a disorder “that is imagined”. He said studies have been done and results published on veterans who have come from Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq suffering from this condition.

Ovuga says the disorder is associated with the experience of overwhelming painful events and could affect almost anybody.

“Although it is not limited to soldiers, they are more at risk because of the painful combat experiences in the bush, Ovuga says, “They are at risk because of the many things they see in combat but also the painful experience they go through during their training.”

Dr. David Basangwa, a senior psychiatrist and executive director of Butabika Hospital says people who have experienced and survived accidents, floods and terrorist attacks sometimes suffer from PTSD.

“For anyone to say that these soldiers suffer from PTSD, they must have been through that overwhelming experience of life and they must also be re-living that experience—remembering it and may be regretting it,” Basangwa says, “that comes some months or years later”.

But senior officials of the army denied PTSD could be pushing soldiers into the killings.

They say anyone claiming that most of the soldiers that were involved in the killings are returnees from operations in countries such as Central African Republic, South Sudan, and Somalia, are wrong.

Gen. Edward Katumba Wamala, the chief of defence forces recently said “that is a total lie”.

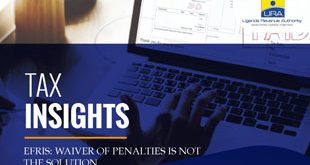

Lt. Col. Paddy Ankunda, the UPDF spokesperson told The Independent on July 19 that, two years ago, the UPDF considered the possibility of post operational stress disorders cropping up and has since established a directorate of mental health.

“However, we cannot look at these actions by soldiers in isolation. We need to trace this strange behaviour from the psychology of our communities. Soldiers don’t fall from heaven; they are drawn from our communities.”

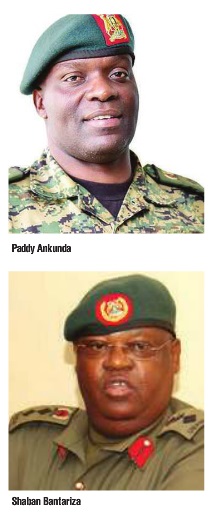

Retired army Col. Shaban Bantariza, the deputy executive director of the Uganda Media Centre, the government’s information bureau has his own theory about the killings. He blames them on “the new breed of soldiers who could be ideologically disoriented.”

“In my view as Shaban Bantariza, a senior officer of NRA/UPDF, what made us psychologically strong and we were able to withstand all the troubles we went through and all the hard times is the political education and ideological training we underwent right from recruitment.

“It gave us reason why we were fighting, how we should sustain ourselves in hard times and how we should keep hope alive,” he said.

Bantariza blames “foreign input” during the recent professionalization process of the UPDF which somehow has left out ideology in the training of recruits.

“To be professional only gives you technical competencies but the attitudinal and behavioural competencies can only come from an ideological foundation; we are not giving it the prominence we used to give it from 1981 to around 2000.”

Bantariza is referring to the early years when many of the soldiers in the current army fought in the rebellion that ended 1986, and some combat in northern Uganda in the early 2000s.

“Why were we not shooting people or even ourselves in 1990 because we had less food, money, uniforms and salary and less everything? Why didn’t we shoot each other?”

“You hear people say they are shooting each other because of alcohol and women but were there no women in 1982?”

He says the thinking of soldiers in 1986 to about 2000 was different and it is the reason no soldier shot a colleague or civilians in bars.

“There is an obvious difference between what we were and what we are today and so we must go back to what we used to be.”

Bantariza says the UPDF should go back to its roots that made it a people’s army and gave its soldiers a purpose for being soldiers at war and kept hope alive.

Bantariza was one of the counselors or political commissars in the army—a role he says used to handle the soldiers’ domestic relations.

Although this position in the army is still there, he wonders whether the office bearers are still as active as they used to be.

“Other than having offices and appointments, how active on the job are they? How many soldiers’ wives take their problems to the Political Commissar and if they do, how does the husband and wife listen to the Political Commissar to solve the problems.”

On why most of the perpetrators are low rank soldiers, Bantariza says it is the leadership at that level (lieutenants and warrant officers) to blame because they are not with the soldiers and are not doing a good job.

“They are not counseling them; they are not keeping them disciplined and busy. We need to go back to what we were before we became what we are,” he says.

He says although there is a unit within UPDF’s medical services dealing with psychotherapeutic needs of soldiers who have just come back from the frontline, he is not sure if they have studied and found out that it is only soldiers from the battlefield who are shooting others.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price