According to experts Dr. Jane Achieng, Dr. Matsihidiso Moeti, Dr Lillian Tugume, Dr John Nkengasong, Dr Mike Reid, Dr Ingrid T. Katz

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT | Uganda is on a steady path to achieving the UNAIDS targets: 95%of people living with HIV knowing their status, 95% enrolled on lifesaving Antiretroviral Therapies (ART), and 95% of those on ART achieving viral suppression by 2025, according to the Minister of Health, Dr Jane Ruth Aceng Ocero.

Dr Aceng struck the optimistic tone in the Ministry’s public message to the nation to mark World AIDS Day commemorated on December 01.

The UNAIDS targets are just two years away. And in the same message Dr Aceng noted that “the country continues to have a big HIV and AIDS burden.”

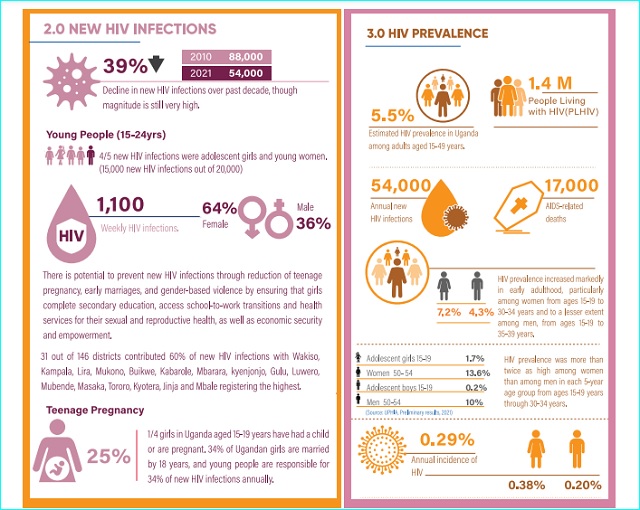

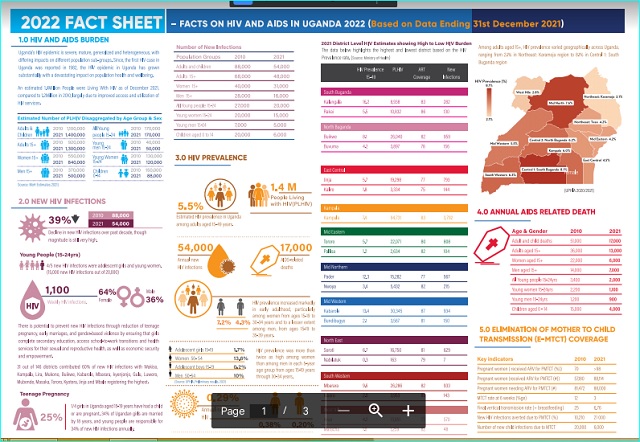

She listed approximately 1.44 million adults and children living with HIV. That is higher than the approximately 1.2 million people aged 15 to 64 that were living with HIV in Uganda five years ago, according to a Uganda Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (UPHIA) for 2016-17.

According to the UPHIA 2020 report that Dr Aceng cites, the prevalence of HIV among adults in Uganda is 5.8%. That is higher than the 5.4% her ministry reported in Health estimates 2020, according to the 2021 fact sheet on HIV and AIDS. It was published by the Uganda AIDS commission based on data ending December 31, 2020.

The UPHIA 2020 report showed prevalence was higher among women (7.2%) than among men (4.3%). The UPHIA 2016-17 report says the prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 64 in Uganda was 6.2%: 7.6% among females and 4.7% among males five years ago.

Comparing the figures over the years from 2016 shows a flat graph, with little change in the critical statistics of prevalence and people living with HIV. The figures show a level of stagnation from the figures that Aceng cites in her World AIDS Day statement.

According to Aceng, “there has been remarkable progress” in relation to new HIV infections.

“We have observed declines in new HIV infections and AIDS related deaths,” she writes, “New HIV infections declined from 80,000 in 2020 to 54,000 in 2022, while AIDS related deaths declined from 68,000 in 2010 to 17,000 in 2022.”

The new infections in 2016 were 51,771 and AIDS related deaths were 28,495, according to the Uganda AIDS Commission’s Uganda HIV/AIDS Country Progress Report July 2016-June 2017. These figures indicate that, to achieve the UNAIDS targets of 2025, Uganda needs to do a lot more and better.

Change in approach needed

Dr. Matsihidiso Moeti, the WHO Regional Director for Africa in her World AIDS Day message emphasised the vital role of communities in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

“In the early days of the response, when the world was in denial, communities spoke up to fight the silence and the stigma,” she said, “As we strive to reach the global targets set for 2025 and 2030, we must create an enabling environment for communities to lead in the HIV response

She was echoing this year’s global World AIDS Day theme of ‘Let Communities Lead’ in recognition of the role individuals living with the virus, families, friends, and activists have had in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

Three health other experts; John Nkengasong, Mike Reid, and Ingrid T. Katz recommend that there is now an opportunity to use behavioural-science approaches to making people, rather than systems, as the core focus of the response to finally ending the pandemic.

Nkengasong is the Global AIDS Coordinator in the U.S. administration of President Joe Biden and Senior Bureau Official for Global Health Security and Diplomacy, Reid is the chief science officer in the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy, and Katz is director for behavioral sciences in the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy.

According to them, behavioural-science approaches are different from early efforts to combat HIV/AIDS that focused on systems-level changes the procurement of drugs, training of health workers and the provision of clinics that were needed to ensure that effective interventions were made available to millions of people. They say these can continue but behavioural-science approaches should be introduced.

Referencing the UNAIDS goal of reaching the ‘95-95-95’ targets, they said whether in relation to testing, antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and other prevention interventions, incorporating behavioural and social science into the design of health-care programmes and making this incorporation mainstream will be essential.

They say health ministries, clinicians, community health workers and HIV activists should be empowered to participate in the design of programmes that ensure everyone has access to life-long HIV care that is centred around the needs of individuals.

Evidence-based strategies to reduce stigma are also crucial especially for those experiencing discrimination on multiple fronts, for instance because of their age, gender, sexuality, HIV status or ethnicity.

At the community and individual level, these strategies can involve using social networks to spread messages about interventions or recruiting people who have experienced their own challenges while living with HIV to talk to and motivate others. Independent monitoring of the quality of care received by those living with HIV is also key to improving services and lessening stigma and discrimination.

As new prevention tools, such as the drug cabotegravir which protects people from HIV infection for up to two months after being injected into the body become more widely available, health-care schemes must be designed so that those who are most likely to benefit from an intervention can access it.

Targeting young girls

“Most new infections occur in adolescents and young adults. So efforts should prioritize young people specifically, girls and women aged 15–24 and men aged 25–35,” they say.

They say, efforts should also continue to prioritise those who would benefit most from preventive treatments such as PrEP, including girls and women, sex workers and members of the LGBT+ community (people from sexual and gender minorities).

“These people might not be aware that they are at high risk of contracting HIV, or realise the degree to which PrEP could protect them,” they say.

They note that as HIV infection becomes less common globally, it has becoming more challenging to reach the individuals and communities that continue to be severely affected by HIV/AIDS.

According to them, testing is crucial. This will enable people to be linked to treatment and also to raise awareness about the possible preventive measures available to those found to be infected and their partners.

They say there is compelling evidence that beginning antiretroviral therapy quickly ideally on the same day as getting a diagnosis increases the likelihood of a person taking the therapy, and of continuing to take it throughout their life.

According to them, globally, an estimated 5.5 million people are living with HIV but are unaware of their status.

According to them, young people, aged 15–24, account for around 27% of new HIV infections globally. But in eastern and southern Africa the region of the world most severely affected by HIV only 25% of girls and 17% of boys between the ages of 15 and 19 underwent HIV testing in the past year.

They say there are numerous barriers that prevent people from getting tested and from receiving timely antiretroviral therapy. These include anticipated or encountered stigma and discrimination, both in clinics and in the broader community, the logistical challenges of getting access to care or collecting medication, and the possibility of inciting anger and mistrust in partners or family members. They say those who are most likely to benefit from various prevention strategies often feel the least empowered to access them.

Several mutually reinforcing interventions that support people to change their behaviour can help to reduce the time between diagnosis and a person starting antiretroviral treatment. These approaches include providing people who have tested positive for HIV with text messages and other reminders to make appointments at their local clinic, ensuring that people can get to the clinic by public transport, and providing incentives, such as monetary rewards, for starting treatment.

According to them, several studies over the past decade have indicated that young people, and others at greater risk of fearing and experiencing stigmatization and discrimination, benefit from having choices.

They need to be able to select the combination of prevention or treatment interventions, the medication pick-up location and the frequency with which they take the drugs that work best for them.

“Establishing youth-friendly health services can also help with this,” they say, “This might entail training and supporting staff to better understand the decision-making processes, sensitivities and perspectives of young people or providing services that are easy for young people to access while juggling school, employment, family responsibilities and so on.”

They cite a study published earlier this year where researchers offered girls and women aged 18–25 information to help them with decision-making in a primary health clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. The information package included youth-friendly information and images of various prevention interventions. The uptake of PrEP among this group was more than 90%, and after one month, twice as many people were continuing to take it, compared with the group who received standard counselling.

In another example, in 2020 researchers provided 500 men in Cape Town with a card containing information about how antiretroviral therapy can prevent an infected person from passing HIV to their partner or family and inviting them to get HIV testing at a mobile clinic. The messaging strategy almost doubled the number of men who came to the mobile clinic for free HIV testing.

A meta-analysis by another group, which included data from 47 studies conducted around the world, showed that leveraging social networks to improve case finding (the discovery of new cases and the determination of who is at risk) is a useful and cost-effective way to reach adolescents and youth. “Leveraging social networks involves identifying certain people as being important in a social network, and then encouraging them to motivate sexual partners or those in their social networks, who might benefit from testing, to test for HIV,” the experts say.

They add that, partly because of the results of the meta-analysis, the WHO now recommends that countries increase their use of testing approaches that utilize social networks.

Reducing AIDS deaths

Another study whose findings are published in the journal PLoS Global Health by Dr Lillian Tugume and colleagues at Makerere University Kampala focuses on how Uganda can continue to reduce AIDS deaths.

According to them, this requires improvements in HIV diagnosis and treatment initiation – and better adherence to treatment and retention in care

They say it is critical to ensure that people with HIV/AIDS do not end up being hospitalized with advanced HIV in the era of universal antiretroviral treatment.

According to UNAIDS, 630,000 people died of AIDS-related illnesses in 2022, compared to 1.3 million in 2010

The researchers say reducing hospitalization due to advanced HIV requires a greater focus on TB preventative treatment, a faster transition of patients to dolutegravir-based treatment and evaluation of long-acting injectable treatment with cabotegravir and rilpivirine to see whether it overcomes adherence problems and reduces treatment failure in their setting.

Their finding are based on research they conducted in Kiruddu National Referral Hospital in Kampala to learn more about why those hospitalized with advanced HIV might have ended up in this situation. The research was done on people with HIV with CD4 counts below 200 or symptomatic HIV admitted to Kiruddu between November 2021 and June 2022.

They interviewed people with HIV or their next-of-kin after admission to hospital about their treatment history and adherence to drugs.

The study recruited 353 adults, the majority of whom had already been diagnosed with HIV. Almost two-thirds of those already diagnosed were taking antiretroviral treatment when they were admitted to hospital, and 40% of all participants in the study had been on antiretroviral treatment for at least six months.

The most common diagnosis in people admitted to hospital was tuberculosis (TB), followed by crypto- meningitis, oral, pharyngeal or oesophageal candidiasis or a bacterial infection.

They found that people admitted to hospital after starting treatment differed in several respects from people with no antiretroviral treatment history. Previously treated people were somewhat older (39 vs 35 years) and had higher CD4 counts.

Analysis of HIV treatment history showed that people who had been admitted to hospital after being on treatment for at least six months were more likely than people on treatment for shorter periods to be taking a regimen containing a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor or a protease inhibitor and less likely to be taking dolutegravir in people on treatment 3-6 months.

They were more likely to report sub-optimal adherence (missing at least two doses in the previous month) and more likely to be unable to report what antiretrovirals, if any, they were taking at the time of hospital admission.

They noted that not taking dolutegravir and poor adherence were the critical factors leading to the admissions. The researchers say that more research is needed on the use of long-acting antiretroviral treatment in people with advanced HIV and treatment failure.

Although poor retention in HIV care is widely recognised as a problem facing fragile health systems, with estimates that up to one-third of people who start treatment are lost to follow-up, it’s less clear what proportion subsequently die or end up in hospital with an AIDS-related illness.

As most admissions were attributable to tuberculosis, the investigators say the other major factor that must be addressed is strengthening tuberculosis preventative treatment in people with advanced HIV. Even though people with HIV in this study had been taking antiretroviral treatment for at least six months, it did not appear to protect them against the development of TB. The WHO has set the target that 90% of people with HIV should receive a TB preventative treatment (TPT) by 2025, according to a report by Aidsmap.com.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Hi, I find the blog informative, though… nice work… do share such information. I’ll bookmark your website.It was such a wonderful and useful article about the HIV infection. It is a must-readable blog to know the brief details of HIV infection.This information is so helpful for me.