How Uganda became anti-homosexual champion of the world

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT | Without downplaying the anxiety over economic and other sanctions by the West over Uganda’s recent passing of the amended Anti-homosexuality law, in a surprising twist, a major fall-out might not be local but international as sexual rights advocates now fear more African countries are likely to copy and use it as a blueprint.

President Yoweri Museveni on May 26 signed into law the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, 2023 that imposes capital punishments to same sex relations, engaging in same sex activity with children below 18 years, engaging in same sex activity when HIV+ and promoting homosexuality.

Same-sex relationships have been a crime in Uganda for a long time, as a legacy of colonial law by the British and successor government, but the new law broadens its definition and makes the penalties harsher.

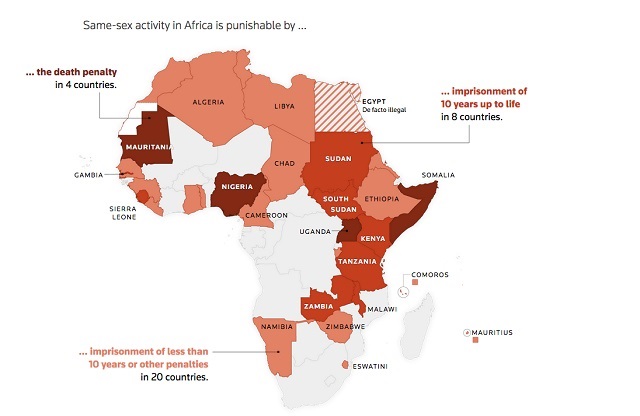

As a result, the new law has been described as one of the harshest for sexual-related offences. It puts Uganda among a select four countries that provide for a death sentence for the crime of homosexuality. The others are Mauritania, Nigeria (under Sharia law) and Somalia.

Most of the commentary on the signing of the Anti-Homosexuality law is similar to what was there even before Parliament passed the Bill on May 02. The discussion has mainly focused on provision for the death penalty for certain forms of “aggravated homosexuality” and a 20-year jail term for “promotion” of homosexuality.

“When you carry out acts of homosexuality through force or duress or undue influence, then the law defines that as aggravated homosexuality. And what is the punishment? The maximum punishment is death,” says MP Asuman Basalirwa (Bugiri Municipality) who sponsored the Bill.

“Under this law, consent is not a defense. The law is saying that the fact that you have consented is in itself not a defense,” Basalirwa adds.

Criminalisation of pro-gay activism

Experts say, however, that this discussion of the law has obscured a discussion of a similarly insidious aspect of the legislation; the criminalisation of pro-gay activism and the providing of “aid or assistance” to LGBTQ+ persons.

“This criminal penalty, the first of its kind in the world, serves as a dangerous model for other countries attempting to legislate against homosexuality,” says Adam J. Kretz, author of `The future of homosexuality legislation in Africa’ and longtime commentator on Uganda’s anti-homosexuality legislation.

In earlier discussions, Kretz pointed specifically at the criminal offense of “promotion of homosexuality” which carries a prison sentence from five to seven years for anyone to “fund or sponsor homosexuality or other related activities” and to use any electronic device, including mobile phones, “for purpose of homosexuality and promoting homosexuality”.

“This wording is so extensive that the law makes Uganda the first nation in the world to codify a multiyear prison term for a straight person who espoused a pro-gay viewpoint,” he says.

The new law makes Uganda the first nation on the African continent to criminalise activities in civil society that “aid and abet” homosexual persons, including renting a room to known homosexual individuals or participating in a demonstration advocating for gay rights.

Kretz says though criminal penalties included under the Uganda law for those who engage in same-sex sexual activity, including acts as seemingly innocuous as a hug between two men are insidious, the inclusion of heavy punishment for mere expression of pro-LGBT sentiments and actions serves as a far more dangerous threat.

“Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill may ultimately serve as the linchpin for a widespread bootstrapping down of LGBTQ+ rights and pro-LGBT attitudes, across Africa and abroad,” he says.

He concludes that a major outcome of this law will be the strapping of long-term attempts to create the necessary structures in civil society that can foment a homegrown gay rights movement in Uganda.

According to research by the Pew Research Centre, acceptance of sexuality rights of LGBTQ+ people are on the rise but opposition remains, especially outside of the Americas and Europe. And the profile of the majority anti-LGBTQ+ individuals is clear; they are conservative, less educated, older, religious, Black, and poorer.

Up to, 129 countries worldwide, 22 of them in Africa, have legally affirmed LGBTQ identities, according to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA). An increasing trend of acceptance has been driven in part by younger people who have adopted more accepting views toward homosexuality.

A 2019 study by Pew Research Centre found that in 22 of 34 countries surveyed worldwide, people aged 18-29 were significantly more likely than their older peers to accept LGBTQ people in society.

Disapproval of homosexuality, however, remains pervasive in Africa. A Pew survey for the Pew Global Attitudes Project puts disapproval of homosexuality at greater than 90 percent for many nations on the continent, with Mali (98 percent), Senegal (97percent), Nigeria (97 percent), Uganda (95 percent), and Egypt (95 percent) showing particularly high levels of disapproval.

Even a majority of South Africans, 64 percent, agreed with the Pew Research statement that homosexuality should be disapproved of by society.

An Afrobarometer survey titled `Good neighbours? Africans express high levels of tolerance for many, but not for all’ showed a large majority of Africans are intolerant of homosexuals. Across the 33 countries, an average of 78% of respondents said they would “somewhat dislike” or “strongly dislike” having a homosexual neighbour.

According to the survey, Ugandans were among those who strongly disapproved having a sexual minority neighbour. Ugandans had only a 5% tolerance for homosexuals; same as in Niger and Burkina Faso. Guinea has only 4% tolerance, Kenya 14%, and Nigeria 16%.

The Cape Verde archipelago of the West African coast was the most tolerant of homosexuals at 74% and all other most tolerant countries were in southern Africa; South Africa (67%), Mozambique (56%), Namibia (55%), Mauritius(49%), and Botswana (43%).

The status of laws placed on LGBT persons by the 57 states in Africa vary from South Africa – which became the first country in the world to constitutionally ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and, in 2006, became just the fifth country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage – to countries such as Sudan and Mauritania that punish homosexuality by death.

Only 15 African countries do not explicitly bar homosexuality by law: Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, South Africa, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Madagascar, the Central African Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Mozambique.

Homosexuality is illegal in 35 countries, seven additional countries have banned male homosexual activity but allow same-sex sexual activity between women. All these countries have laws against homosexuality, with penalties ranging from fines, to corporal punishment, to prison terms of varying lengths, and, finally, death penalties.

Just days after President Museveni signed the Bill into law, a Ugandan who signed off as DeLovie Kwagala, a non-binary (person who does not identify as either male or female) photographer and activist, wrote an article in The Guardian UK newspaper titled ` I’m heartbroken at my exile from Uganda. Don’t let them erase our queer community’.

“I’ve documented the realities of queer life in my home country for more than seven years,” the Ugandan wrote, “Now the anti-homosexuality bill, which was signed into law by President Yoweri Museveni on Monday, makes both my art and my existence punishable by jail, or even death”.

“We’re sending funds to contribute towards costs such as bail for those imprisoned, emergency accommodation, legal and medical fees, visa and transportation costs for those leaving the country,” the article concluded.

Kretz says: “Uganda’s attempt to strengthen criminal penalties, up to and including multi-year prison terms, for even minor forms of both public and private pro-LGBT activity is exceptional. Already, the immense public popularity of the country’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill has resulted in the introduction of near-identical draft laws in parliaments from Nigeria and Cameroon”. Other countries such as Liberia, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Zambia are pursuing equally tough measures against same-sex relations.

Reaction to the Bill

After passing the Bill on May 02, Ugandan MPs jubilated, cheered, and danced in the House. Leaders of religious faiths, both Christian and Muslim, congratulated Speaker Anita Annet Among who corralled the MPs into speedy debate and passing of the Bill.

“As Parliament of Uganda, we have heeded the concerns our people and legislated to protect the sanctity of family,” she said, “We have stood strong to defend the culture, values and aspirations of our people.”

Soon after President Museveni signed the Bill into law on May 26, he was praised by politicians and ordinary citizens alike.

Three days after President Museveni signed the Anti-homosexuality Bill, 2023 into law, however, U.S. President Joe Biden issued a statement calling for its repeal.

Biden’s statement on May 29 said: “The enactment of Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act is a tragic violation of universal human rights—one that is not worthy of the Ugandan people, and one that jeopardizes the prospects of critical economic growth for the entire country. I join with people around the world—including many in Uganda—in calling for its immediate repeal. No one should have to live in constant fear for their life or being subjected to violence and discrimination. It is wrong”.

Biden said the Anti-homosexuality law is the latest development in an alarming trend of human rights abuses , corruption, and democratic backsliding in Uganda that threaten Ugandans, U.S. government personnel, donors, tourists, the business community, and others.

He added: “As such, I have directed my National Security Council to evaluate the implications of this law on all aspects of U.S. engagement with Uganda”.

Biden listed the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), American assistance and investments, Uganda’s eligibility for the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), and sanctions and restriction of entry into the United States.

Biden said the U.S. Government annually invests in Uganda nearly $1 billion (Approx. Shs3.7 trillion which is about the same amount allocated to the Uganda Transport and Works Sector in the proposed 2023/24 budget). This investment is at stake over the anti-homosexuality Bill.

Leaders of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), in a joint statement on May 29, said there “are deeply concerned about the harmful impact of the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023 on the health of its citizens and its impact on the AIDS response”.

The leaders included Winnie Byanyima, a Ugandan who is Executive Director, UNAIDS, and Under-Secretary General of the United Nations.

Germany’s Development Minister Svenja Schulze told DW, a Dutch broadcaster, that “the law has an impact on the work of international partners on the ground, which we must now examine together.”

Frank Schwabe of Germany’s ruling Social Democratic Party (SDP) warned that Uganda is abandoning the shared values of the international community and those of the African Union.

“The country is putting itself on the sidelines and will certainly also feel the economic effects. The law must be repealed immediately,” Schwabe reportedly told DW.

“They are going to look for us, they will kidnap us so we might go in for life imprisonment. That is why you are seeing everyone not talking. They are quiet, they are very annoyed, we are not safe not at all. We are now just going to ask for asylum and leave the country because now it seems like everyone is against us. If the president has signed we have to look for asylum in countries which will allow us,” a lesbian in Kampala to DW.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023 states some, but not all of, the following punishments:

• A person convicted of the “offense” of homosexuality is liable to life imprisonment

• Attempting a sexual act with someone of the same sex is punishable by up to 10 years in prison

• Those convicted of “aggravated homosexuality,” meaning sexual acts with minors, or people with disabilities or HIV, face the death penalty

• Anyone who advocates, celebrates or openly discusses LGBTQ-related issues faces up to 20 years in prison for “promoting homosexuality”

• Any person who does not report acts of homosexuality will be fined up to Shs 50,000 (US$13) or up to six months in prison

Timeline to passing the Anti-homosexuality law

Prior to 2000: Male-male homosexual activity was banned by law, and could result in a short prison sentence and fines, and female-female homosexual activity, while not illegal, was met with severe social stigma.

2000: Revisions of the nation’s penal code in 2000 made all homosexual activity illegal and punishable by life imprisonment. This made Uganda one of the worst places in the world for antigay laws.

2009: David Bahati, in his first term as MP introduced the Anti-Homosexuality Bill of 2009, also called the “Kill the Gays Bill, that would make Uganda the most unwelcoming place for LGBT persons, or anyone harboring support for LGBT persons. It introduced the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality,” or any sexual encounter with a minor, disabled person, person who is HIV-positive. It criminalised anyone who “aids, abets, counsels, or procures another to engage of acts of homosexuality,” punishable by up to seven years in prison. Condemnation by world leaders, including Ban Ki-Moon, David Cameron, Barack Obama, Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, and others caused it not to be passed by parliament.

2010: David Bahati brings his Bill back to the floor of Parliament but it fails to be passed again.

October 2010: Ugandan newspaper Rolling Stone published the photos and names of what it called “100 known homosexuals” under the headline “Hang Them!”.

2011: Speaker Rebecca Kadaga pushes to pass the Anti-homosexuality Bill but Parliament completed its business on May 13, 2011 without discussing the Bill.

2012: Speaker Rebecca Kadaga vows to pass the Anti-homosexuality Bill as a “Christmas Gift” to Ugandans. But the Bill is not passed.

December 2013: Parliament passes Anti-Homosexuality Bill.

February 2014: President signs Anti-Homosexuality Bill into law.

March 2014: Ugandan rights activists and politicians filed legal challenge in the constitutional court to overturn the Anti-homosexuality law.

August 2014: The Constitutional Court annuls Anti-homosexuality bill saying it was passed without the requisite quorum and was therefore illegal.

October 2019: The Sexual Offenses Bill is tabled in parliament.

May 2021: Parliament passes Sexual Offenses Bill, which contains a clause to criminalize same-sex relationships.

March 2023: Parliament introduces new anti-homosexuality Bill.

May 02, 2023: Parliament passes the new Anti-Homosexuality Bill, 2023

May 26, 2023: President Yoweri Museveni signs Anti-Homosexuality Bill, 2023 into law.

May 29, 2023: A group of 11 activists petitioned the Constitutional Court seeking to challenge the Anti Homosexuality Act of 2023.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

It’s time for the government to utilize it’s natural resources than getting worried of international aid.