Museveni should know better

Goobi says the budget expansion to Shs40 trillion is a mistake and Museveni, who has been in power for around 33 years, should know better what happened in the past when governments were spending everything in the treasury.

“He should not be making the same mistakes,” he told The Independent.

Ggoobi says the problem is worse because the government is drifting further and further away from the best situation; where the money the government collects in tax revenue and donor budget support is equal to what it spends, to a worse situation where it is always looking to borrow to spend more and more.

This year, since donor support to the budget is nearly zero due to corruption; over Shs20 trillion of the budget will be funded through borrowing.

Of the Shs20trillion, Shs7trillion is coming from external lenders and about Shs15trillion will be borrowed locally.

This is worsening the country’s debt situation and killing domestic businesses and social services.

According to the Public Finance Management Act, 2015, the domestic borrowing limit for government is capped at 10% of domestic revenues. That means this year’s domestic revenues of Shs15 trillion, can only support government borrowing of Shs1.5 trillion. However, government is looking to borrow 10 times more.

Experts are warning that the economy could pay a high price. The 2018 report by the parliamentary committee on national economy, for example, cautioned that government domestic debt is constraining funding to the private sector.

To understand how critical private sector credit (PSC) is to economic performance, one looks at years when the economy has performed poorly and when it has performed well.

In 2008 when the economy performed at its best— slightly over 10%, PSC grew at 49.4% between June 2007 and April 2008.

In 2013 when the economy posted worst performance since 1991, PSC had fallen from an average of 33% to 4.5% in September 2012 and sluggishly picked up to about 8.8% as of September 2013. In 2017, the economy was still struggling—no wonder PSC only grew at 2.8%. The current wave of recovery was supported by a PSC annual growth of 10.5% as of last year.

But the new plan by government to increase borrowing internally could reverse this positive trajectory.

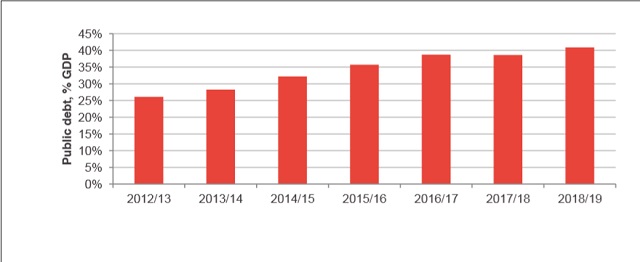

By end of June 2018, the total public debt stock stood at Shs41.3 trillion which is equivalent to 41.5% of the country’s GDP. The level of debt as a percentage of GDP was 26% in 2012 and went to 32% in 2014, and 40% in 2018. The more debt has grown, the more it has eaten into the budget.

Sharp raises and deep cuts

Next year, for example, Treasury Operations which deals with domestic debt refinancing, was allocated Shs9.5 trillion – bigger than any ministry, government department or agency. The other big takers will be the Works Ministry (Shs5.3 trillion up from Shs4.7 trillion) and Security (about Shs4 trillion).

Budget allocations to other sectors—social sectors—are set to dip. For instance, the Health budget is being cut from Shs2.3 trillion to Shs2.2 trillion and Education from Shs2.7 trillion from shs2.6 trillion, according to details in parliament’s Budget Committee report on the National Budget Framework Paper. These figures could further change given that officials at Finance are still tinkering with the budget.

Uganda has over the years suffered the cost of domestic borrowing. Between 2012 and 2018, Uganda’s economic growth limped on at about 4%.

Trouble started in 2012 when Uganda passed the Anti-homosexuality Act and angry pro-gay Western donors reacted by cutting budget support.

Rather than cut spending, the government, which previously only borrowed domestically for monetary policy objectives, started raising cash for financing the budget through domestic borrowing.

Consequently, interest on treasury bills reached 21%. Banks smelling profit shifted a lot of their lending from the private sector to government and also increased their lending rates.

Because lending to government is less risky, most banks limited their lending to the private sector, those that did, charged exorbitant terms—sometimes in the region of 30%.

In some cases, companies that had borrowed at lower rates all of a sudden had to pay more than what they had initially borrowed at. Many began to default and even collapsed. The biggest victims were banks.

By 2015, three major banks suffered major losses as a result of Non-performing Assets. Those backed by international benefactors got recapitalized and survived. Locally owned Crane Bank, which was the biggest lender to local businesses, was not as lucky.

The economy shrunk even further—hitting the lows of 3% growth.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price