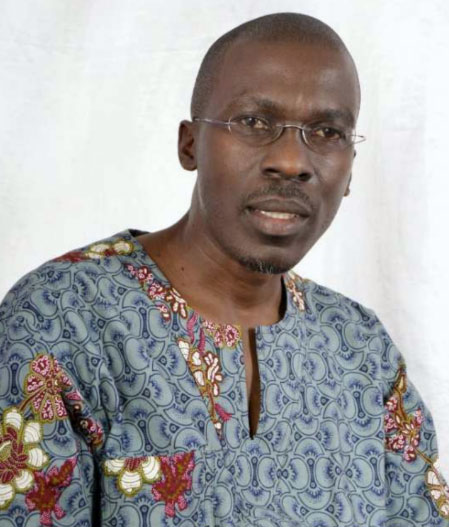

As Uganda celebrates 63 years of independence, attention turns to how the country has navigated its economic journey and positioned itself within East Africa’s integration and global economic agenda. The Independent’s Julius Businge spoke to Julius Kapwepwe Mishambi, a member of the East African Budget Network (EABN) – a professionals’ platform on EAC integration and economic affairs – about independence, economic resilience, oil, and Uganda’s role in regional competitiveness.

QUESTION: Uganda has now spent more than six decades as an independent nation. From an economic perspective, what stands out most in this journey?

ANSWER: Uganda’s independence in 1962 was a defining moment, with our forefathers and mothers having fought for our country back through resistance, that we earned control over its political and economic choices, just like other struggles by all other present day EAC States. We are talking about a journey from the time when Uganda basically depended on an enclave economy (island of wealthy 9% population amidst 91% in a sea of poverty) in 1962 and GDP of less than $3.5 billion (1986), to about $9.6 b (2004). Today we are doing all the economics arithmetic and will achieve at least a $66b GDP by the time of a new government come May 2026, to anchor the country to over $500 b by 2040, fifteen years away from today. That is steady progress and also a peace dividend that was elusive for Uganda between 1962 to 2006 when finally the last rebel group out of 56 then was defeated by NRA/UPDF and entire country pacified. The said $66 b GDP in 2026 has clearly been built under good stewardship of H.E. President Museveni steward over very few decades, since nearly half of Uganda’s other time in post-independence has largely been under chaos, with actual time for work under total peace and general security being between 2006 and 2025. The significant positive strides in energy quantity and outreach, expanded national roads and DUCAR network, agro-industrialization, urbanization, expanded free and accessible immunization of children and mothers, revamping and expansion of domestic production of consumer goods have led to Uganda’s better human capital and healthcare outcomes. Even so there have been missed opportunities like no modern standard gauge railway and Kishwahili for greater EAC integration. Governance challenges that influence the economics of the day also remain withstanding. It is a protracted struggle and a luta continua for equitable prosperity for all Ugandans.

Q: Uganda’s economy has transitioned from being heavily reliant on agriculture — particularly coffee — to a more diversified base with emerging sectors like oil and tourism. From your perspective, has this diversification been sufficient to create sustainable growth, and what key sectors should Uganda prioritize over the next decade?

Economic diversification and search for socio-economic transformation have been central to NRM’s policy direction. Uganda has expanded from just six major commodities in 1988 to about 30 by 2025, Tourism has transformed — from dilapidated parks to now thriving attractions like the Uganda Martyrs Shrine in Namugongo, the Kasubi Tombs, and Gulu University and beautiful Katikekile hills across the Karamoja plains and horizon, with projected earnings of $2 billion (UGX 7 trillion) by September 2026, from a paltry $662 million, just after the 2002- 2009 European credit crunch period. For long-term resilience, Uganda must upscale export promotion and import substitution, moving toward a self-integrated economy. Ugandans themselves must play a central role in wealth creation by investing directly through shareholding in both private and government-backed companies. This ensures dividends are reinvested domestically instead of being lost to capital flight. Then Uganda will have a self-integrated textiles sector, from cotton seedling quality- to farm- to processing- to finally all textile products domestically here. Then cotton seed products (oil, livestock feeds and more) and there will be no more textile import- export problems.

Q: How would you assess Uganda’s economic performance in the context of East African integration?

Uganda’s story cannot be told in isolation from the East African Community (EAC), the Great Lakes region, the Economic Community of Central African States (e.g. Chad and Central African Republic) or even the Maghreb that hosts North African economies like Algeria and Mauritania. All those are desperate for Ugandan consumer goods like soap, sugar, foods stuffs, industrial ware (tiles, cement, steel products, milk products, Ugandan organic coffee taste and more).Taking the United States, COMESA, Association of Southeast Asian Nations or unified Germany examples, regional integration is a key opportunity for us as EAC, if we learn and act together. Integration expands our strategic security, forces us to a common strategic plan, markets. Real integration – not lip service and excuses – means trade barriers and political espionage diminish; to give way for strengthened collective bargaining for inter-state projects rather than just disjointed economies in Africa. Shell BP with net income at $42.4 billion in 2022 excluding her global capital assets, dwarfs nearly the EAC combined $ 313 billion GDP in 2022.

Yet this EAC GDP is perforated with debt overweight and Kenya leading in the sovereign debt burden. But yes, Uganda has benefitted from regional infrastructural projects, the customs union, and the common market. Implementation gaps and non-tariff barriers including bad roads still slow our progress. Our competitiveness as a nation is closely linked to how well we embrace specific regional value chains and deploys private sector capital to supplement EAC Governments, in their domestic and cross-border investment frontiers.

Q: With commercial oil production set to begin next year, Uganda faces both opportunities and risks. What policies or safeguards must be in place to ensure that oil revenues drive inclusive development rather than exacerbate debt and inequality given that public debt levels are above 51% of GDP?

Oil presents Uganda with a major opportunity for capital formation through skilling, technology transfer, expanded stock of infrastructure, and enhanced balance of payments. Rising from $590 million (Shs2.1 trillion) annually today already, to about $850 million (Shs3 trillion) in the medium term. Risks nonetheless do exist, particularly around regional insecurity and the threat of rebel groups, whether domestically, Central Africa, the Sahel or even Margreb when you consider the unfinished liberation business under Polisario Front in Western Sahara areas as broad potential trade avenues for Uganda. Oil is not just a domestic affair but a regional security matter, requiring Uganda and its neighbors — South Sudan, DR Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi — to strengthen joint security apparatus, through the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and the East African Standby Force frameworks. On the fiscal side, Uganda’s debt has financed infrastructure and expanded the stock of public goods and services, under energy, roads, education, health, NARO research expansion and others. Despite its limitations, public debt has and will still yield long-term economic dividends if well managed.

By 2027, Uganda expects to join OPEC, thus have a voice that influences global business, politics under Non-Aligned Movement and EAC political outlook, which surely contribute to boosting her revenues and scaling debt to manageable size. Already guided by Vision 2040, the Parish Development Model, and National Development Plans, Uganda aims to progressivel reduce debt and inequality while channeling oil revenues into inclusive growth and economic resilience.

Q: Compared to Kenya, Tanzania, and Rwanda, Uganda still lags behind in industrialization and manufacturing competitiveness. What reforms would help position Uganda as a regional powerhouse over the next 20 years?

Uganda’s competitiveness will hinge on strategic industrial hubs like the Kabalega Industrial Complex, which includes over six major projects and serves as both an economic and logistical bridge for the Great Lakes region. This is complemented by Nile Equatorial Lakes Subsidiary Action Program (NELSAP) investments that link oil, water resource management, and regional trade. To fully unlock its potential, Uganda should commercialize agro-industrialization; fasten the construction of the standard Gauge Railway, expand mineral processing, then manufacturing with a strong emphasis on transformative dividend and green economics. The tax regime must be streamlined by removing unnecessary burdens on domestic businesses and reducing income tax for lower categories of people and SMEs. Uganda must also prioritize value addition in coffee and a few other strategic commodities by shifting from raw exports to processed and packaged products for Middle East and Gulf, far Asia, EAC and other segmented global markets. Another unique strength is its secure “night economy,” which can be more advertised and leveraged as a driver of investment and tourism. Finally, strengthening anti-corruption efforts will be essential to safeguarding EAC integration, while building on the economic and political gains already achieved.

Q: Uganda’s private sector often raises concerns about the cost of doing business. How can independence milestones help reframe this debate, and how should government sustain Uganda’s low cost of doing business to attract investment?

Independence anniversaries remind us of the unfinished agenda. Reducing the cost of doing business requires deliberate reforms — better infrastructure in strategic areas like logistics, streamlined regulations to deal with fake inputs and inferior products, more affordable credit, and reduced government bureaucracy in public service. The private sector must also be enticed more to invest in Uganda and EAC, be innovate, adopt modern technology, and harmonise regional policy for more trusted collaboration. Uganda already enjoys a low cost of doing business within the EAC and Great Lakes region, but we are at the starting line. With the right reforms, it can become a regional economic powerhouse, driving manufacturing, energy, agro- industry, and services.

Q: Over the next decade, what priorities should Uganda focus on to not only achieve its economic goals but also ensure meaningful transformation in the lives of its people?

Uganda’s development priorities over the next decade should continue to focus on human capital development through skills training and citizens’ shareholding into companies to boost capital formation. Value addition is essential, particularly in sectors such as iron ore from Muko in Kigezi and Nkore, where a robust steel industry could serve regional markets. Government-led investments in Osukuru fertilizer opportunity, Kilembe mines, and expressways through public- private partnerships and public shareholding will be critical. The dairy sector must expand so that Uganda’s position as Africa’s leading milk producer translates into 100% processed domestic products and exports. Tourism can be accelerated with projects like Kihiihi International Airport, which would attract direct inter-continental flights and maximize revenues from gorillas and tree-climbing lions. The oil sector holds promise through initiatives like the Kabalega Industrial Park, a refinery, and storage facilities expected to generate over $10 billion (UGX 35 trillion) annually. Regional integration projects such as the oil pipeline and reverse gas imports from Tanzania will balance economic growth with green energy development.

Q: Looking ahead, what message would you give Ugandans about independence and economic integration?

Independence should not just be about political sovereignty but about economic dignity of all the people across gender, creed and regions. Even the 19 refugee nationalities we host here as Uganda must feel safe, loved and economically rebuilding themselves. Ugandans should view the EAC and AfCFTA not as distant policy projects by heads of State only, but as strategic security and economic opportunities to expand business horizons, create “Ubumwe”, jobs, expanding and building households and corporate wealth. Integration works best when citizens, professionals, and businesses participate actively, not just government bureaucrats and politicians of the day. Integration is a matter of interests for all citizens to appreciate. At 63, Uganda’s next frontier is to guard political, economic and social cohesion gains this far.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price